by Jon Gabriel Pallugna Villanueva

Stepping outside felt like stepping into an alien world.

I was among the last set of people that the government let out since the pandemic begun four years ago. The doctors, the government, and my family refused to let me out. You’re HIV positive. It’s too dangerous. There were times, though, that I wished I could venture into the outside world for air, sunshine, and interaction.

There was only so much that a computer could see, or a computer would tell. Videos and calls and endless clicking could never even begin to describe and replace the pleasure of being held or touched. Still, I don’t have much to complain about. I wasn’t in the worst position that I could be in. At least I wasn’t dead or halfway there, right?

They tell me that my cousin died last year. Complications from a longtime weak immune system, bundled with this new blood-thickening virus was the final nail in the coffin. I hear that my aunt couldn’t even have her daughter be buried; the body was burned too fast, and with too short of a notice. There was nothing to put in the ground.

I didn’t even know that she died, at first. I went off social media for a few months, tired of the terror and anxiety it would cause. You’re next, it always seemed to tell me. Mom broke the news the same morning she told me to wear black. We sat there, staring into a video feed of an urn being carried, until the ashes were finally spread over some beach somewhere. In all honesty, I can’t say that I feel the same grief that my aunt probably does. The last time I saw my cousin was when we were seven. We’re both nineteen now, or at least, I am. I don’t know if they count when you’re dead.

Nothing about my cousin dying felt real. Maybe that’s why I’m so apathetic. I’ve seen hundreds of pictures of dead people and funeral announcements on facebook; I’ve read through obituaries that only seemed to grow longer at the peak of infections. Nothing about my cousin felt real or special. She was just another obituary I would read about this Sunday, the only difference being that our family paid for newspaper space. My aunt was too grief-stricken to even think of doing it herself.

I don’t know what she’ll do after this, really. No amount of grief will change the fact that there was one less daughter in her family of seven. I suppose she’ll pick herself up after all this. It’s not like she has much of a choice except to move forward, after all. But now wasn’t time for that, at least for her. She was entitled to mourn the way a mother does when she has to bury her own child.

I wish my cousin didn’t die though, if I’m being honest. Now all my parents worry about is how anything and everything in the outside world could kill me, as if I was some newborn child in a world where everything was a loaded gun pointed at my head. I’m not some tower of cards, I wanted to tell them. But they were right, the way parents often are, even when they’re being over-the-top. The world could kill an ordinary person back then, it would be a death sentence for me.

I imagine that the pandemic changed me, somewhat. I’m not sure where or how exactly, but it probably did. Solitude with only a computer in front of me and a family of nurses I couldn’t see without a screen between us, much less hug, did things to me. I’m willing to bet that I wasn’t alone in this. Everyone went through something under lockdown. Why else would plants and baking supplies sell so well?

First came the denial. Everything would blow over in two weeks. This was all just a massive overreaction over something that would be gone soon. The media absolutely loved blowing things up, after all. Next came the anger. What was wrong with China? What was wrong with the government, just letting the cases go up and up? Someone was supposed to care, and that someone certainly shouldn’t have been me. That feels like a lifetime ago, now. I was sending out character after character, pound sign after pound sign in an endless fury of hashtags that social media loved to use. We all knew deep down, of course, that there wasn’t anything we could really do. But we felt angry, confused, and furious at ourselves for being powerless. The fury had to go somewhere.

Bargaining was when I bought an oven. It’s just a short-term hobby for now. It’ll come handy in the future, I bet. Maybe if I found something to keep me occupied, things would blow over much more quickly. For better or for worse, the collective malaise was pushing hundreds if not thousands of us to the very same places for the very same items. Everything that I once used to grab off the shelves in the supermarket was being delivered to my house—through credit card, of course. We couldn’t risk infection, as if handing over a few bills and coins was a mortal sin that would demand retribution.

Going off social media came just as depression began to sink in. There was too much on the news. Bad governance, deals gone awry, and people dying by the minute. Stronger and stricter lockdowns happened in the course of time, but nothing much changed for me. I was still stuck within the same cemented walls that seemed infinitely high whenever I would step to the front door. I believe people called our place a compound, but I don’t think they’re entirely right. It was only us that ever lived here, and I was sure that compounds meant many people and large families. Compounds meant people, and people meant someone to talk to. Either way, it’s not like I had anyone else to ask. I had no messaging services, after all.

Buying plants and being labelled as the plantito was acceptance, I suppose. I was in this for the long haul; I might as well have some form of life when all that was beyond the gates of our home was the looming shadow of death. It was therapeutic, in a way. The greens in pots under the sunlight were photo-worthy, even if those photos only ever existed in my mind and in my phone—only meant for me to see.

But today is finally the day when I’m free of that. The claustrophobia, the fear of the virus floating in the dark at night, and the solitude when seeing familiar faces across the screen.

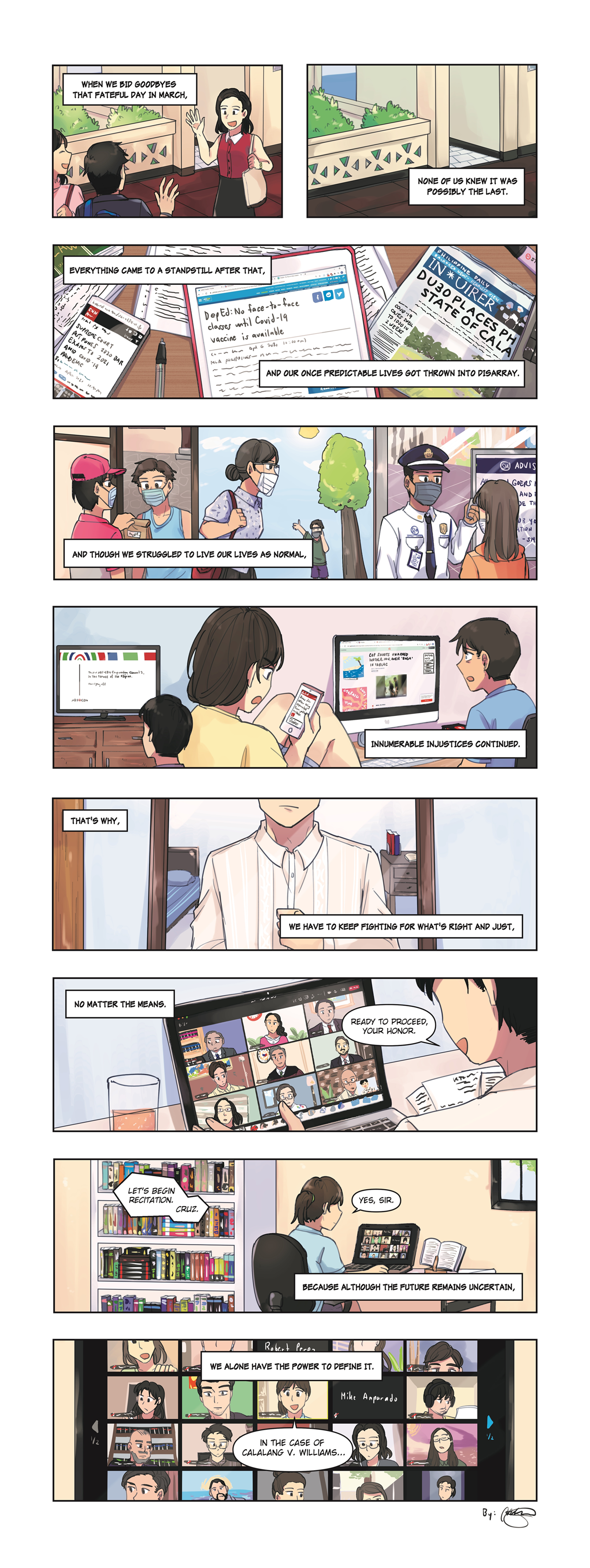

But everything feels different now, doesn’t it? The air is crisper, the trees are thicker, and there’s no tension in the air that makes you ask if it’s okay to breathe. I remember at some point that there was a debate on social media about whether or not nature was healing when humans were gone. Many called it a massive lie, but now I’m beginning to wonder if that’s true.

My friends are just a train ride away. I’m surprised that somehow, someone had managed to build a massive new station just nearby. I’d heard about it, but it’s still hard to grasp about how something so massive, and something so imposing with its concrete columns could just prop under my nose. I can’t help but notice that all the shops I used to go to are gone, too. The foot of the station starts at the ground floor of a mall that’s been here since time immemorial, but none of the familiar sights are there. There’s no milk tea, no restaurants, no hobby shops.

The train itself feels so much different, too. There’s the smell of alcohol and disinfectant in the air still, perhaps a remnant of what could be considered a darker point in history. People always say that landmark events in history change how things go forever from thereon out; a revolution gave us a new constitution, technology gave us new ways of interaction, and a pandemic gave birth to disinfectant being sprayed in all our public places. Still, there’s little choice on what to do. Change is inevitable, and it’s just something people have to get used to.

There’s an awkwardness that wasn’t there before between strangers, I can tell. If this had been years ago, people would have rushed over to pack themselves like sardines. Now there was this respect for personal space that I would have never even begun to fathom if it were years ago. No one was touching each other, each in their own respective little space. I’m not sure if it’s because of them or if something has changed altogether, but the train is somehow colder. Everything is somehow whiter. Everything, though familiar, is ever so slightly different.

I see my friends across the station, the first time I’ve actually seen them in years. We would talk every day over the phone and see each others’ faces across the screen, but this would be the first time we’d actually meet in person in a very, very long time. There’s not much for us to catch up on, since we seem to be invested into every minute detail of anything interesting that might have happened across the screen. They’re sitting across each other awkwardly, not knowing that I’m already close by. I can see that there’s some form of social ineptness as they awkwardly gesture and laugh, as if they had lost that bit of themselves when they had been inside for four years.

I suppose I’ll have to cope with that too in a few minutes. They’re finally waving at me, after all. In a few minutes, I’ll most probably be the just as awkward as they are as we exchange clumsy hugs. Perhaps there was something different about them that I couldn’t see yet, and there was something that changed about me that I had yet to know. Everything and everyone had changed ever-so-slightly when everyone was locked away within their homes, like a picture that’s just a touch out of focus.

This morning, it felt like the world was alien. That’s still true, even now. But things are slowly coming into focus, the way that it does when you come back to a neighborhood you used to live in: strange places become familiar piece-by-piece, the bends in the road suddenly make sense, and the whole place seems to finally come back to memory. Perhaps this world was still the same place that I left, just changed, but not replaced. But that’s the sign of landmark events in history, isn’t it? It changes things forever.

I suppose that this time around, it’s my turn to live with the change and get used to it. All I can do now is keep moving forward, hoping for a better future.

After all, there isn’t much choice but to keep on living.

on the upper right corner to select a video.

on the upper right corner to select a video.