by Jon Gabriel Pallugna Villanueva

When I was twelve and at our mother’s funeral, Ellaine had asked me what people felt when they died. “I don’t know,” I told her. “Maybe mom knows.” Years later, I imagine that she found out. Her neighbors found her hanging by the balcony at four in the morning, just a few weeks after she had just turned thirty-five.

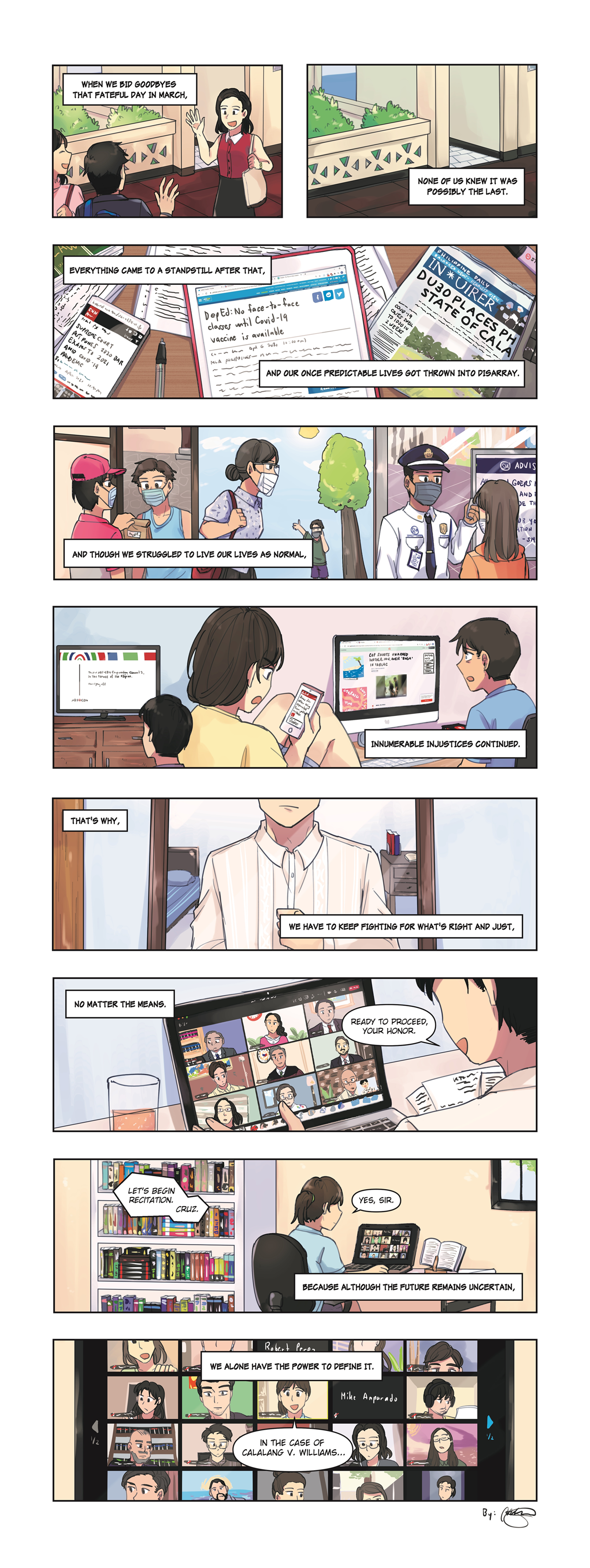

If it had been just business as normal, I would have packed my things and gone home to the family home in the Philippines. But things were far from normal—they still are, actually. I can’t say that I couldn’t understand why she killed herself, if I’m being honest, although I’ve had some dark thoughts myself in isolation. I remember a quote from an old movie I can’t quite remember the title of: When people are isolated from human contact, their minds can do the most bizarre of things. Seventy-two hours without contact is enough to drive someone insane, imagine months of it in an empty home.

We weren’t always alone. There were three of us siblings left when mom had passed away. Dad took care of everything at the time, from contacting the funeral home and making the arrangements for a plot that was only half-paid. When he passed on two decades later, it was our turn to hold vigil. As kids, we didn’t know what to make of things when our mother passed away. Facing the loss and mortality of the woman who raised you was a form of waking up that other children don’t experience until really later in their lives. Still, we already knew about death, dying, and the afterlife. Mom had been a devout Christian when she met dad at church. We, as often children do, still held the same values they had raised us on.

We were ready when Dad passed away in his sleep. Every child, even if they don’t say it, realizes at a certain age that they would have to bury their parents. It’s considered an inconsolable tragedy for any mother or father to bury their own child who failed to outlive them, after all. But in all my pondering about death, I had never thought about burying a sibling.

The last time I saw Ellaine was seven years ago, when I had to go home because dad had died. I told myself when I was moving abroad that I would go home every year, multiple times if I could. Things were much simpler then—I was a young bachelor who had the time, energy, and lack of relationships abroad to let me keep my promise. I used to fly back to the Philippines four times a year at first, the homesickness getting the best of me. Still, the more invested I got in work, the less I could go home. The more relationships I had, the less I missed the cramped quarters of my room in the Philippines.

Four times a year turned into two, then only once during Christmas, to every other year when I could. When I met my wife, only the boxes went to the Philippines. As if to compensate, the balikbayan boxes grew in size the less I was able to fly home. It was easier to do, especially when the box was the only one going to the Philippines. I could only bring small boxes home with me, but anything too large was too inconvenient to carry and transport from the airport. There was some solace in sending the lone balikbayan boxes at home, at least. A little less of me felt meant more of a balikbayan box, and a smaller balikbayan box meant more of me. At least they were getting more chocolates.

A video call or a Christmas card would have to make do in lieu of my presence. They cared less and less about me coming home too, if it was any consolation. Paul had started his own food truck business, pointing to fondly to the fact that he was the best cook among us three. Several multimillion investments later, and we barely see him. Ellaine found herself enamored with someone and music, joining a local conservatory to teach people like her. I’m still surprised they didn’t get married after all their years together.

Still, we shared a bond like all siblings do. Years of not talking to each other could be filled within minutes of laughing and seeing each other, the mental bond and fortitude of growing up together. Now there was one less sibling between us, and a new conversation topic about a sister who once was. I can’t even begin to think about what I’ll tell other people. “I had my mom, dad, and two siblings,” I can imagine myself telling. “But my sister killed herself a while back.”

I’d been talking to Ellaine as of recent, you could say, just before she died. A couple of sporadic video calls here and there when I wasn’t in another meeting, often while I drank coffee in the storage room that we converted into an office a few months ago. I let her prattle on about so many things, the way she did when we were kids and she just got home from school.

I never paid much attention to the signs, but retrospect always has infuriatingly perfect vision. Her long-time boyfriend left her after her second miscarriage, the music classes felt fake over zoom, and the food was starting to taste bland. There were times she would feel out of it, repeating conversation topics from before and being surprised whenever I would say that we’ve been through this. I’ve heard that depression could cause memory loss, but I wasn’t even sure if she was. It certainly didn’t feel like it, with the way she always had an upbeat voice. Thinking about the aftermath of everything, maybe she did. Maybe I just didn’t notice.

I remember how things unfolded that day. It started with getting a call from an unknown number as I was brushing my teeth in the dark next to the master bedroom, trying not to wake up my wife, and my daughter who snuck in when we were sleeping. The voice was gruff on the other end of the line, but the matter-of-fact way of talking was unmistakable.

For a moment, I’m taken back to my childhood and the pranks you play on your siblings who seem like the most annoying people in the world at that age. You’re always able to tell if one of them is playing a trick on you over the phone, which is why it will never be them on the other line—it would always be a friend or a bored cousin you don’t meet often.

It was a surprise at first that he called me. I hadn’t talked to Paul in forever. I considered looking up his email on his company website or calling his office phone at a time that neither of us would be busy at, but I put those away every time, telling myself I would do it next time. Who knew that the first time we’d talk in years would be him telling me that my sister had killed herself in the house we grew up in?

Planning her funeral was something we didn’t have to do much of, thankfully. Everything from her funeral, her wake, and settling of estate had been planned beforehand. Paul tells me that everything that needed arranging had been put in a brown envelope over the kitchen table, with a sticky note noting what had been arranged and what hadn’t been. There was no suicide note, no last words for us to ponder on. All she left was a manila envelope with a list of bullet points of what we had to arrange ourselves, an indignation in and of itself that she was still the same matter-of-fact sister we had knew her as growing up.

Ellaine had always been the meticulous type, refusing to leave any room for uncertainty. I still remember back when Ellaine was in her third year of high school, pulling on her hair the way she did when she was stressed as she looked through the catalogue of courses each university offered. I was a junior myself in college, having shifted once from an engineering degree to another engineering degree in the same university.

“You don’t have to worry that much. You can shift two or three times without getting worried.”

“Easy for you to say. You’re always the smartest person in the room.”

“Bold words, coming from you.”

She smiled the slightest bit then, trying to control the edges of her lips creeping up into a small grin. She loved being complimented, especially when it was about her intellect. She was always a bit odd, I suppose, in that sense. She would roll her eyes whenever someone would call her pretty, maybe the occasional sigh of exasperation.

“That’s all so superficial,” she’d say.

The wake and funeral were far removed from the times we did it with our mom and dad. Back then, far-flung relatives and strangers of all sorts came. Most of them carried stories with their condolences, about how dad used to be a rambunctious brat who would run around the neighborhood with a pack of dogs at his heels, or how mom used to be the talk of the town for being the first in her family to graduate college.

Ellaine, Paul, and I would often joke about it ourselves when no one else could hear us.

“Guys were falling all over for mom. Guess it doesn’t run in the genes,” Paul would say coyingly at Ellaine.

“That’s true,” She would retort back. “When are you getting married?”

The funeral was much quieter this time. There were no stories, no drunken laughter by old friends of the dead, and no cries of frustration at the mahjong tables we’d place in our small garage as we scrambled to serve food from the kitchen. Very few people came to the funeral, and the atmosphere was heavy and somber. I could tell even from across the screen.

The immigration officials wouldn’t let me go to the Philippines. A travel ban was in place, they had told me. No one leaves and no one is allowed to enter the country. “We’re sorry, sir,” They told me in their apologetic retail voice. “But those are the rules.”

Dejected, all I could do was watch every night as the funeral was held on stream on facebook. I wonder what Paul would tell other people about Ellaine. People will ask and people will talk about what happened, no doubt. Perhaps he would know better than I. He was closer to Ellaine than I was.

My wife and my daughter sit next to me as they lower her coffin into the ground. The pastor had finished presiding over the funeral of four attendees and two cemetery workers who cranked the lever that squeakily lowered the box of my sister. Paul stood at the edge of the camera feed, the mandated distance that health regulations prescribed for us to hold this in the first place.

I talked to Paul after the funeral then, him complaining about the heat under the noonday sun and how lucky I was to be sitting in my bedroom, probably with my suit over a pair of shorts. It was unspoken then, that this would be the end of our conversations. Ellaine had given us a reason to connect again, but now that was done and finished. Us siblings had all been tangled up at some point in our lives, and untangled the next. Now we were tangled with one of us dead, and the other two in the dark about why. It was probably time again to untangle.

I can’t help but wonder why she did it. My mind keeps drifting back to mom’s funeral, when she asked me of how dying felt. I still don’t have the answer, but maybe Ellaine did know now, wherever she was. Another part of me feels a bit guilty that maybe I if I had been there better for her, she’d still be here. Paul let out a sigh when I told him about it.

“She’s dead. Does it even matter?”

Didn’t it? I was sure that being out of her life and out of her hair played a part in everything. At the end of the day, she wrote to us siblings, and to no one else. Maybe Paul did have a point, about why it didn’t matter anymore. It was too late for her, after all.

A person who dies, no matter how thorough, will always leave some form of sentiment in the people left behind. Ellaine was no different. The last thing she ever thought about was family, the way she put the sticky note on the manila folder before she tied the noose around her neck. Maybe we could have been there, the way we siblings would hold each other up when we were younger. Maybe if things were the slightest bit different, we would be laughing over a cup of coffee sometime when quarantine ended. But Paul is right—it doesn’t matter anymore. It was too late for her now, lying seven feet below the ground. But can the same be said for the living?

Before I know it, I find myself dialing Paul’s number. He’s still not married after all these years, I tell myself as I smile at the memory.

By the time I hear the now familiar gruff voice on the other end of the line, I already know that the balikbayan box going home to the Philippines is going to be small when the lockdown is finally lifted.

on the upper right corner to select a video.

on the upper right corner to select a video.