by Jenny Domino

It is very likely that social media will serve as the battleground for posts that can run into vaguely worded penal provisions under the [Anti-Terrorism Law], such as the crime of ‘inciting to commit terrorism.’ This should not be a problem in a rights-respecting democracy; independent courts can make a determination of illegality after observing due process guarantees.

As Facebook’s Oversight Board begins to hear cases, do courts have a lesser role to play in resolving questions of speech?

This week, Facebook’s Oversight Board has invited public comment for its first batch of content cases. The Board is the global body that will decide hard content questions on Facebook and Instagram. CEO Mark Zuckerberg announced the company’s plan to create the Board in late 2018, after facing international scrutiny for the Cambridge Analytica scandal, foreign electoral interference in the 2016 US presidential elections, and Facebook’s role in Myanmar’s Rohingya human rights crisis, among others. According to Zuckerberg, this oversight mechanism would help hold Facebook accountable to the public. The structural independence of the Board has been carefully laid such that legally, financially, and operationally, the Board is not part of Facebook-the-company.

Facebook appointed the first set of Oversight Board members in May this year, and the Board announced in October that it would start accepting cases. The first set of posts up for review involve content issues that have haunted social media for years — hate speech, violence and incitement, adult nudity. One post involves a question on the relatively more recent “dangerous individuals and organizations” policy of Facebook, which received previous scrutiny. The initial cases were referred to the Board by aggrieved Facebook users. Out of over 20,000 referrals, these cases made the cut based on various criteria determined by the Board.

Is the Oversight Board like a court?

The Oversight Board takes up cases just like a court would, but it also issues policy advisory statements that a court does not do. Users can refer cases to the Board after exhausting the appeal process within the platform, provided the impugned content satisfies other criteria on difficulty, significance, and impact. Facebook can separately refer cases to the Board. For now, the Board only handles posts that Facebook removed from the platform, but this will soon extend to leave-up decisions.

The applicable “law” of the Oversight Board is Facebook’s content policies, and to an extent, international human rights law (here, I describe why diversity matters in interpreting and applying these applicable “laws,” and why the Board’s composition is not diverse enough). Facebook is bound by the Board’s decision on individual cases.

What of courts?

One type of content expectedly excluded from the jurisdiction of the Oversight Board concerns posts adjudged illegal under local law (e.g., Philippine law). States generally reign supreme within their territory, but state sovereignty comes with certain obligations as part of the international legal order. This includes human rights protection. International human rights law forms part of Philippine law, and the Philippines is bound by its international law obligations to protect human rights.

Businesses are also not exempt from responsibility. The soft-law United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights provide a standard of conduct for companies like Facebook to “respect” human rights. Companies cannot invoke state authority to evade this responsibility. This would require them to consider whether compliance with certain laws and requests from the State is in itself human-rights compliant.

It is in this context that many human rights defenders have raised serious concerns with the newly enacted Philippine Anti-Terrorism Law. It is very likely that social media will serve as the battleground for posts that can run into vaguely worded penal provisions under the statute, such as the crime of “inciting to commit terrorism.” This should not be a problem in a rights-respecting democracy; independent courts can make a determination of illegality after observing due process guarantees.

Law and code

In his book, The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom, Yochai Benkler calls the current information ecosystem we inhabit the “networked information economy,” a successor of the industrial information economy dominated by commercial mass media. According to Benkler, the high cost of technological infrastructure in the industrial era limited information providers to mass media companies with the financial resources to do the job. This, in turn, encouraged “lowest-common-denominator” cultural production that catered to large audiences across the board, and generally bred passive consumers.

In contrast, the networked information economy, with its low cost of access, has not only enabled a more dynamic way of reacting to information provided by mass media, it also fosters a “generative” culture where users with various distinct interests can connect with peers and, simultaneously with traditional media, become active participants in creating and distributing content.

But problems of control similarly beset cyberspace. Lawrence Lessig emphasized the interplay between law and code in his classic texts, Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace and Code: Version 2.0. It is not only lawmakers that control what we can and cannot say and do, code – as designed by engineers and proprietors – also controls the architecture of cyberspace. Lessig put it succinctly— “code is law.”

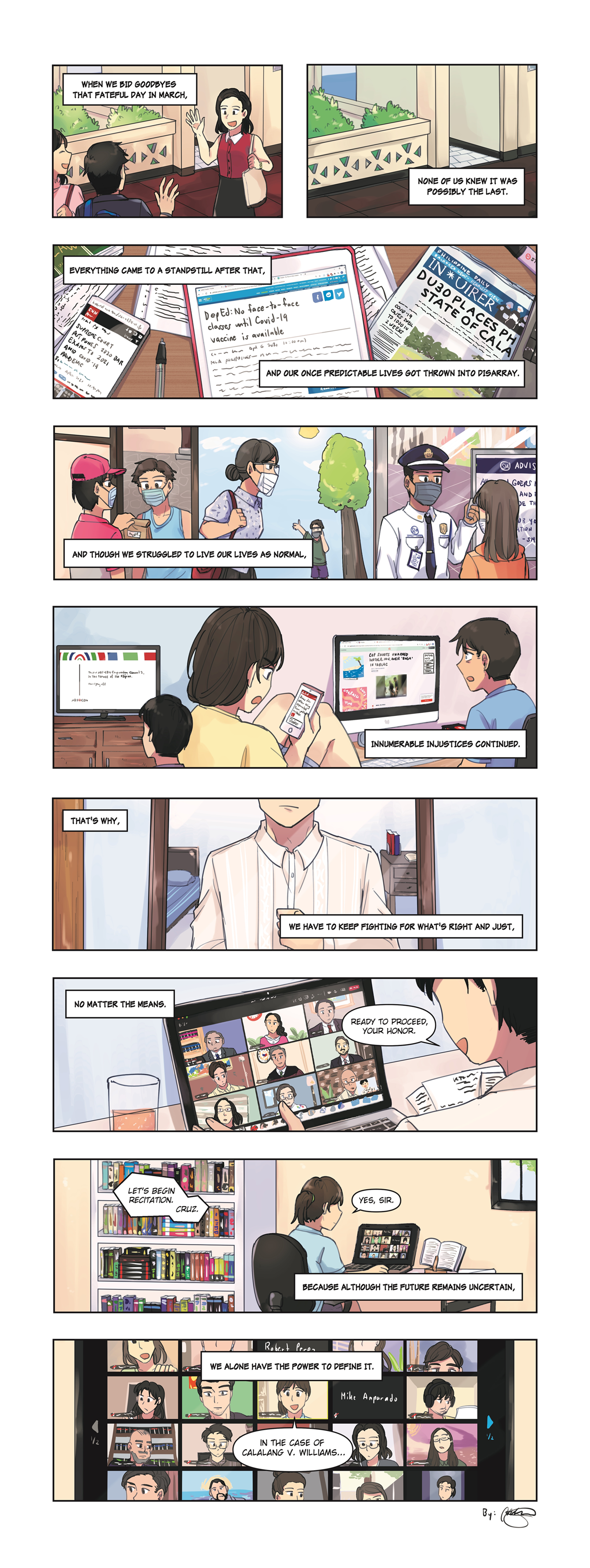

Nowhere is this issue more salient than in a time of a global pandemic that has forced people to move their lives online, and in no small part on Facebook. Law tells us what we cannot say online (no incitement to sedition, no defamatory statements, no incitement to terrorism, etc.), but so do social media companies within their own enclosure (no hate speech, no coordinated inauthentic behavior, no dangerous actors, etc.). Private policy (Community Standards), enforcement (content moderators removing, labeling, downranking, leaving-up posts), and adjudication (user appeal and the Oversight Board) overlay our legal speech framework. In response, pundits have begun to explore how existing legal concepts – ranging from fiduciary duties to dispute resolution processes – can apply by analogy to social media regulation of speech.

In her book, Between Truth and Power: The Legal Constructions of Informational Capitalism, Julie E. Cohen invites us to pause in drawing comparisons. In a public sphere defined by scale, microtargeting, infoglut, and virality, Cohen points out the gaps in individualized justice and court procedural design, products of the industrial era. Lawyers must grapple with these questions – among many – as the networked information economy continues to evolve.

What of rights?

Last month, the Forum on Information and Democracy published a policy framework for fighting infodemics (disclosure: I authored the second chapter on adopting human rights principles in content moderation). The report was framed mindful of the fact that in many jurisdictions, “architects of networked disinformation” are state-sponsored or state actors themselves. The chapter on incorporating human rights principles in content moderation further articulates the work of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on freedom of expression on the topic. Some recommendations reflect the changes that dominant social media companies are already implementing.

More needs to be done. One recommendation is better transparency. Another would require social media companies to conduct ongoing human rights due diligence to identify at-risk situations based on assessments made by public democratic institutions. Examples of at-risk situations are countries experiencing natural disasters, armed conflict, or elections. These moments usually generate intense social media activity, a potent recipe for misinformation. Instead of fixating only on content, the report recommends social media companies to tweak content responses that would make it harder for misinformation to go viral. This approach recognizes that given the scale of content moderation, not all content issues can be resolved in time. Prioritizing content problems based on potential adverse human rights impact is key.

In Myanmar, Facebook recently implemented time-bound rules on hate speech and misinformation in the context of national elections held last month. Local civil society reported that Facebook has done better, though there is a long way to go to rectify the company’s previous wrongdoing.

As technology evolves, law has to improve along with it. To effectively protect human rights in the networked public sphere, we first need to understand the background against which these developments are taking place. As Cohen’s book powerfully shows, that includes the role of law – its fictions, procedures, and contractual terms – in facilitating the change. – Rappler.com

Reproduced from: https://www.rappler.com/voices/thought-leaders/opinion-role-courts-era-content-moderation

on the upper right corner to select a video.

on the upper right corner to select a video.