‘A basic rule in political law is that a candidate for public office should have all the qualifications and none of the disqualifications for office.’

There are statements making social media rounds that view the qualifications of Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. — his eligibility to run for President — as a political question. The argument goes that a political question cannot be decided by the Commission on Elections, and ultimately by the Supreme Court. This is incorrect.

These statements also promote the view that a candidate (Marcos) who is leading in election surveys cannot be disqualified, ostensibly, because the people will be deprived of their choice for President. This is also incorrect.

Both views are supposedly grounded on the “political question doctrine.”

Political questions are those questions which, under the Constitution, are to be decided by the people in their sovereign capacity or in regard to which full discretionary authority has been delegated to the legislative or [to the] executive branch of the government (Mamba v. Lara, G.R. No. 165109, Dec. 14, 2009). These are questions that are left for the people themselves to decide or which are to be decided by the other branches of government.

Political questions are concerned with issues dependent upon the wisdom, not legality of a particular measure (Estrada v. Desierto, G.R. Nos. 146710-15 & 146738, March 2, 2001).

Where the controversy refers to the legality or validity of the contested act, that matter is definitely justiciable or non-political (Sanidad v. Commission on Elections, G.R. Nos. L-44640, L-44684 & L-44714, Oct. 12, 1976).

There is no Supreme Court decision saying that a candidate’s eligibility for public office is a political question.

An issue is not a political question simply because votes are cast by the electorate. In Miranda v. Aguirre (G.R. No. 133064, Sept. 16, 1999), the Supreme Court held that a plebiscite to approve Republic Act No. 8528 (downgrading the City of Santiago from an independent component city to a component city) is not a political question. The issue in that case was whether Republic Act No. 8528 complied with the requirements of the Constitution which is a question that the Supreme Court alone can decide.

A basic rule in political law is that a candidate for public office should have all the qualifications and none of the disqualifications for office.

A person who garners the highest number of votes in an election, if disqualified under election laws, cannot be declared the winner. The Supreme Court has been very clear on this.

In Maquiling v. Commission on Elections (G.R. No. 195649, April 16, 2013), the Supreme Court held:

The ballot cannot override the constitutional and statutory requirements for qualifications and disqualifications of candidates. When the law requires certain qualifications to be possessed or that certain disqualifications be not possessed by persons desiring to serve as elective public officials, those qualifications must be met before one even becomes a candidate. When a person who is not qualified is voted for and eventually garners the highest number of votes, even the will of the electorate expressed through the ballot cannot cure the defect in the qualifications of the candidate. To rule otherwise is to trample upon and rent asunder the very law that sets forth the qualifications and disqualifications of candidates. We might as well write off our election laws if the voice of the electorate is the sole determinant of who should be proclaimed worthy to occupy elective positions in our republic.

Then in Halili v. Commission on Elections (G.R. Nos. 231643 & 231657, Jan. 15, 2019) the Court held that:

Where a material COC (certificate of candidacy) misrepresentation under oath is made, thereby violating both our election and criminal laws, we are faced as well with an assault on the will of the people of the Philippines as expressed in our laws. In a choice between provisions on material qualifications of elected officials, on the one hand, and the will of the electorate in any given locality, on the other, we believe and so hold that we cannot choose the will of the electorate.

Maquiling also emphasized that the qualifications prescribed for elective office cannot be erased by the electorate alone. The danger of allowing the election results to erase election laws was spelled out in the same case:

What will stop an otherwise disqualified individual from filing a seemingly valid COC, concealing any disqualification, and employing every strategy to delay any disqualification case filed against him so he can submit himself to the electorate and win, if winning the election will guarantee a disregard of constitutional and statutory provisions on qualifications and disqualifications of candidates?

If this is the rule — if a candidate who garners the highest number of votes can be disqualified — it should also apply to a person whose claim to the popular mandate has not been tested in an election.

The idea that popularity in an election survey converts a legal issue into a political question is preposterous. If we adopt this view, Beyoncé can run for President of the Philippines because her popularity will trump the requirement that the President should be a natural-born citizen of the Philippines. Or American actress and singer Zendaya no longer has to meet citizenship, age, or residency requirements of the Constitution (Article VII, section 2 of the Constitution).

The pending disqualification cases against Mr. Marcos should be resolved by examining the allegations against him, and by determining with impartial minds, whether Mr. Marcos has all the qualifications and none of the disqualifications for holding public office. The popularity of a candidate, however measured, should never be a factor in settling these disputes. – Bworldonline.com

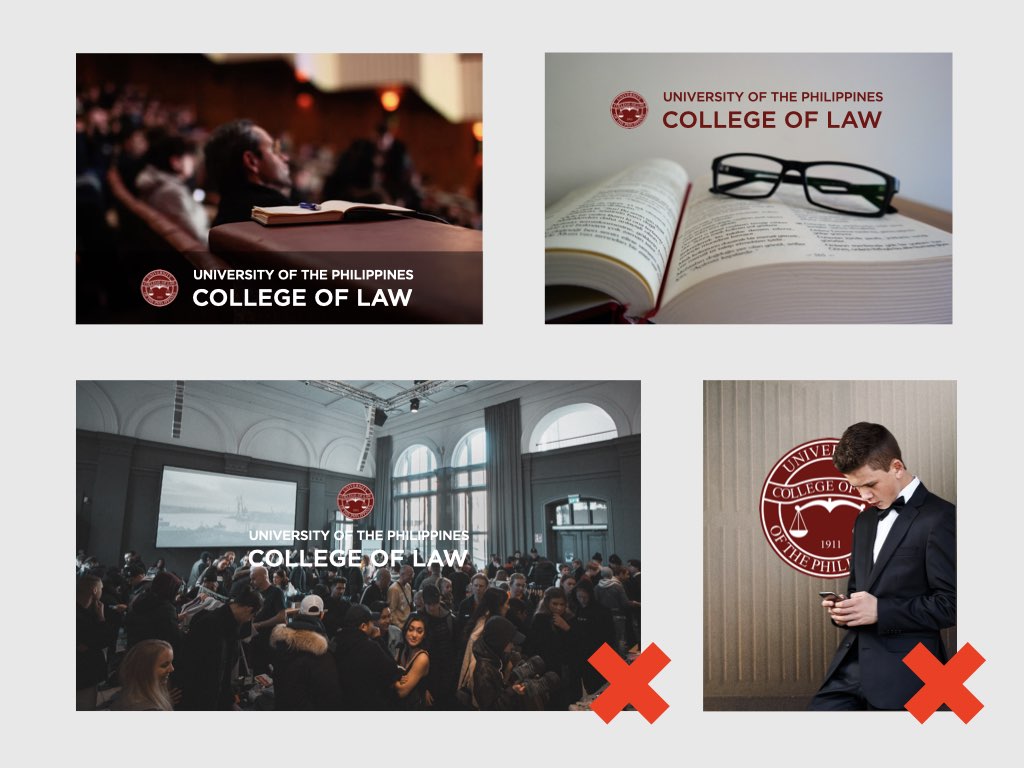

Dante Gatmaytan is professor at the University of the Philippines, College of Law and a fellow of Action for Economic Reforms. This article was originally published on BusinessWorld.

on the upper right corner to select a video.

on the upper right corner to select a video.