Authors: Jay L. Batongbacal, JJ Disini, Michelle Esquivias, Dante Gatmaytan, Oliver Xavier A. Reyes, and Theodore Te

(20 minutes reading time, 6,487 words)

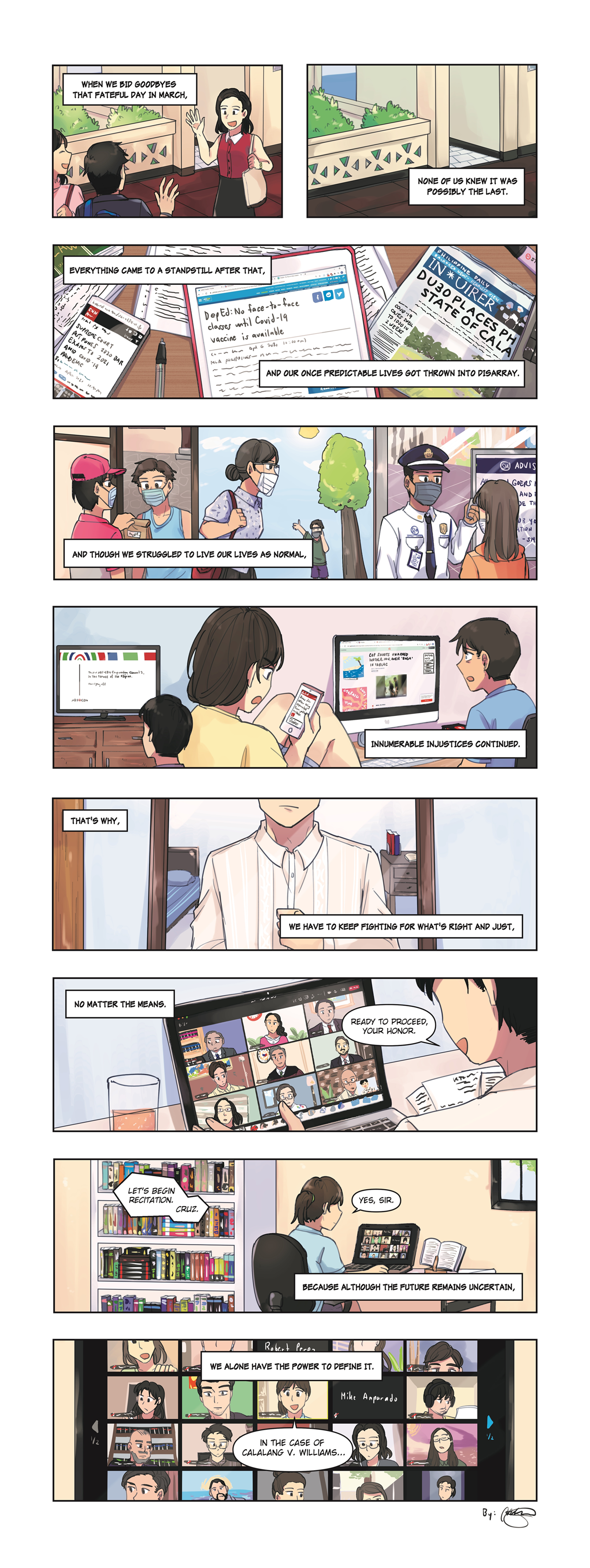

- In this paper, professors of the UP College of Law recommend an implementation framework for temporary alternative court procedures to facilitate the prompt resumption of court proceedings despite the health risks posed by the COVID-19 emergency. This is in recognition of the effects of the pandemic to the judicial system, including its consequences on the efficient operation of the courts to its general impact on the rule of law.

- The authors formulate short-term, medium-term, and long-term approaches to address concerns, with specific suggestions, timelines, mechanisms, roles, and expected output.

- Short-term approaches (May 15 – June 15, 2020) address the urgency of controlling and preventing further spread of the virus, at the same time deploy available technology solutions without having to change the analog nature of litigation.

- Medium-term approaches (June 15 – September 15, 2020) entail the consideration of interim measures of rules to fine tune the system in place or the use of hybrid systems to transition of certain legal processes from paper-based systems to online system.

- Long-term approaches (September 15 – December 2020) include overhauling the trial court system to make it more electronic, cloud-based, and more susceptible to participation from a distance.

- The paper also identifies particular considerations in employing the approaches – from identifying parts of the function/rule/process that increase the vulnerability to the virus, to adoption of appropriate technology, to the capacity of the organization, to accommodation of vulnerable litigants.

- Outlining concrete steps forward, the paper proposes the formation of a committee to address the issues and subcommittees to tackle particular challenges. It also outlines the role of the IBP and practitioners and explores coordination with Congress and other actors in the Justice System.

I. Background

The COVID-19 pandemic stopped the world in its tracks. The virus, easily spread through casual contact, forced governments to institute lockdowns and enforce “social distancing” measures to prevent the further spread of the virus. Courts were compelled to shut down to contain the disease.

The COVID-19 pandemic has several negative impacts to the judicial system:

- Courts—particularly the trial courts—cannot operate efficiently during the pandemic.

- All court participants will have concerns about becoming infected in the course of their work. Possibly, many of them are senior citizens whose movements may be constrained even under general community quarantine rules. Some may refuse to work entirely—unwilling to risk their health.

- If the courts were to operate within the constraints of social distancing, court appearances will be few and far between to avoid infections between all litigants and lawyers. Docket processes will have to be modified to prevent the transmission of the virus through court submissions. Documents may need to be stored at a secure location for a number of days to ensure that they are virus-free.

- COVID-19-related problems are particularly pronounced at the trial court level, which relies extensively on face-to-face interactions. This is true because of the nature of the cases that are within their jurisdictions as well as the nature of the acts performed therein such as cross examination and the admission of evidence. Only trial courts receive evidence at first instance and are assigned the exclusive role of assessing the demeanor of witnesses and disqualifying objectionable questions and answers.

- Hence, appellate courts are less susceptible to external COVID-19 health hazards since they almost never interact face-to-face with litigants, save for the exceedingly rare occasions where oral arguments are called. As long as filing deadlines are resumed, and filing/service procedures are restored, appellate courts can return to their prior functions even during the health crisis without need for an extensive change in procedures or rules.

- General impact on the rule of law.

- A judicial system that cannot fully function puts Constitutional rights at risk and disturbs the balance of power among the branches of government. Citizens cannot go to court to question government conduct. Judicial review of executive actions would be impossible without functioning courts, especially suits that require reception of evidence—a function trial courts are specially equipped to perform (Gios-Samar, Inc. v. Department of Transportation and Communications, G.R. No. 217158, March 12, 2019).

- Private rights cannot be effectively vindicated without fully-functioning courts. Compliance with and enforcement of private obligations are already put in doubt due to quarantine measures. Parties to contracts who are injured as a result must have the courts opened to them to vindicate their rights; otherwise the stability of all commercial transactions will be jeopardized.

- The rights of the accused are even more susceptible to violations. Without judicial oversight, abuses such as overstaying prisoners, denials of their entitlement to bail and preliminary investigation, and violations to right to a speedy trial may continue unabated. Access to counsel of choice during quarantine/lockdown is also impaired.

- Private lawyers cannot practice or earn money. Lawyers practicing either by themselves or as part of a firm cannot ply their trade. Unable to render services, they cannot bill their clients and this puts them in dire financial straits. This has spillover effects on their clients, employees, suppliers, and others with whom they transact. This further exacerbates the economic crisis brought by the pandemic and the lockdown.

- The Constitutional guarantee of free access to the courts and quasi-judicial bodies under Article III, Section 11 is impaired, not simply by reason of poverty but also by reason of circumstance, i.e., lawyers are not allowed to travel freely.

_

II. Objectives

This paper recommends an implementation framework for temporary alternative court procedures to facilitate the prompt resumption of court proceedings despite the health risks posed by the COVID-19 emergency. In the course of developing the framework, the paper shall identify gaps in current court procedures and practices that can be addressed by maximizing new technologies and best practices, as to enhance the efficiency and transparency of administration of justice by the trial courts. The paper also identifies potential longer-term reforms to the procedures and practices of Philippine trial courts. Finally, it offers some timelines within which to implement the strategy.

_

III. Policy Strategy

Short-term, medium-term, and long-term approaches must be formulated to address these concerns:

- Mixed approach. Short-term approaches must accommodate the current paper-based system and introduce technology-based measures to prevent or control the spread of the virus. The purpose of this is to address the urgency of controlling and preventing further spread of the virus but at the same time recognizing the existing court system. Portions of legal processes may use new technologies.

- Hybrid approach. Medium-term approaches involving a transition period where some courts leave the paper-based system while others continue to use the same. This could ostensibly entail the use of hybrid systems. The whole value chains of certain legal processes are expected to be transitioned to online systems. During this period, some courts should be able to already shift away from paper-based systems, while some other courts continue to operate on that basis.

- Smart court approach.[1] Long-term approaches may include overhauling the trial court system to make it more electronic, cloud-based, and more susceptible to participation from a distance. This may entail the review of laws and judicial administrative issuances for purposes of incorporating measures that prevent the spread of viruses.

_

IV. Discussion

The following section identifies particular concerns that the proposed approaches must consider:

- What part of a function/rule/process has the potential to spread the virus or cause infection?

- Based on currently available information, the virus is able to survive on surfaces for a number of days. Affected surfaces include paper documents and physical surfaces in courts. There is emerging evidence that the virus may be transmitted through airborne transmissions in certain closed quarters, leading to the recent mandatory rule for the wearing of masks. The opportunities for viral transmission on account of regular court practices and procedures should be definitively identified, so that appropriate mitigation measures can be adopted.

- Paper-based processes need to have a period of storage to allow the virus to dissipate naturally before being transmitted to the courts.

- Potential short-term solution: Allow online submission of pleadings to cloud providers coupled with hard copy submissions at a central point designated by the court where it will be received, stored for a number of days and then transmitted to the relevant branch for entry into the record. This process may be followed for pleadings, motions, submissions, and original evidence.

- What part of a function/rule/process can be remotely provided easily in the short term?

- Physical travel for the purpose of attending hearings, filing pleadings or serving processes creates health risks that can be mitigated through remote accomplishment of these tasks. The 2019 Amended Rules would implement such changes through limited online filing, while conducting trials via video teleconferencing has been allowed for certain criminal cases. Other opportunities exploiting remote accomplishment of tasks or functions should be identified and outlined.

- As a potential short-term solution, videoconferencing equipment and services through commercially available services may be provided for free to the court, the jail and public attorneys by the private sector, i.e., the local IBP chapter. If judges, private lawyers or any other participant can afford to procure their own technology and work from the safety of their own offices or homes, then they may do so. Perhaps it would be fair for the IBP to engage in price differentiation to allow more prosperous members of the bar to subsidize user costs to those starting out, with fewer resources or those providing free legal services such as law student clinics, NGO’s and human rights lawyers.

- What controls are necessary to achieve the goals of a function/rule/process?

- Proposed procedural changes should be consistent with such constitutional rights as due process and the rights of the accused. Other virtues such as integrity and transparency must also be assured. Appropriate controls that safeguard concerns must be designed prior to implementation. These efforts should prevent abuse by litigants and lawyers such as coaching of witnesses, intercalation of documentary evidence, etc.

- As a short-term solution, counsels (and in appropriate cases, their clients) can be bound by undertakings similar to the “signature” requirements in the new Rules. Such undertakings can stipulate that any appearance of a violation of ethical norms will be met with a suspension of the violating attorney’s use of the system and/or the use of the same by his or her entire law firm. For abuses related to having a single camera, the system adopted may install at least 2 or more cameras to show the immediate surroundings of the participant or witness. All sessions will be recorded.

- What rule changes are absolutely necessary and how much of a solution can be provided by contract or binding rules?

- Some proposals may be inconsistent with the Rules of Court and would require amendments approved by the Court en banc for implementation. Certain changes though may fall within the discretion of individual trial courts to implement on a case by case basis and hence would not require en banc approval.

- As a short-term solution, private counsels (and in appropriate cases, their clients) can be bound by judicially-enforced contracts and/or undertakings to abide by the specialized rules to be enforced to facilitate the trial and court processes. In order to allow for the speedy implementation of such special measures, those solutions which can be implemented by mere court order will be identified, with their implementation preferably covered by court-enforced contract/undertakings rather than rules promulgated by the Supreme Court. Local IBP chapters can take the lead in finding their own solutions that fit their needs in their areas. A Circular from the Supreme Court will help especially one which allows for a feedback loop or sharing of best practices.

- What technology is appropriate (cost, ease of use, availability, security) to adopt with a view towards neutrality?

- Certain proposals, such as video teleconferencing, may be implemented using available general-use technologies that may be acquired for low rates. There may be proposed changes that would entail customized systems at greater cost but would also ensure that important concerns such as security and access rights would be addressed.

- As a short-term solution, local IBP Chapters can be asked to determine their solutions based on the availability of infrastructure in their areas and the ability of the users to learn the intricacies of the adopted technology.

- How will the technology (HW/SW/cloud services) be procured and how will operational expenses be paid?

- Fully automated courts and court procedures may be the ideal. However, the establishment of a fully functional electronic court system will take years to design. Deferring the implementation of technology solutions, especially during the COVID-19 crisis, may lead to litigants (particularly detention prisoners) having their fundamental rights violated or the administration of justice otherwise being unduly delayed.

- A framework or an implementation plan for the implementation of the “smart court approach” should be developed immediately. Some systems may be procured by the Court already under the emergency procurement policies of the government. An implementation plan ensures that the systems that will be procured are consistent and compatible with the overall plan.

- Another option is provision by private third parties. In this case, the local IBP chapter should be allowed to provide the infrastructure for free to the government agencies involved. Operational expenses can then be defrayed by the legal community, or by litigants, through reasonable access fees for the use of technology-enabled processes such as online hearings facilitated by the IBP or donations coursed through the IBP.

- While the Offices of the Clerks of Court in the court stations can be eventually trained to operate or administer the new systems, outsourcing that role to the IBP or private sector employees may be more feasible as a short-term solution.

- How can we address concerns of those who may not be skilled in using the proposed technologies?

- Older practitioners who may be less adept at using technology as well as judges and court personnel who are used to paper-based processes may find it difficult to transition to an electronic platform.

- As a short-term solution, the service provider, i.e., the IBP Chapter, can provide technical support and training to the personnel concerned. For lawyers who are not familiar with electronic filings, a “service bureau” may be established by the IBP Chapter whereby paper-based documents are scanned and uploaded to the cloud according to the rules established. The cost for these services may be defrayed on a per-user basis.

- The Philippine Judicial Academy (PHILJA) must also be harnessed and mobilized towards equipping judges with the necessary technical training, in the interim and short term, and expertise, in the medium and long term.

- The Mandatory Continuing Legal Education (MCLE) Office must likewise be harnessed and mobilized towards equipping lawyers with the necessary technical training, in the interim and short term, and expertise, in the medium and long term.

- How can vulnerable litigants (detention prisoners, children, victims of VAWC) be accommodated?

- Current rules provide for protection for vulnerable litigants in the form of anonymity or shielding from direct confrontation. These rights have to be complied with in any solution proposed by the Court.

- Current rules on perpetuation of testimony must be highly encouraged, if not made mandatory. These rules heighten the security of any witness as there would be no gain to threaten or kill witnesses who have already testified ahead of trial.

- As a short-term solution, the rules adopted by the IBP, the Court, the litigants and all participants should adhere to statutory requirements protecting vulnerable parties. Video monitoring may, for example, be shielded or the video feed disabled to address privacy concerns.

_

V. Suggestions for Immediate Implementation (Short-Term Approaches)

The following short-term measures are proposed to allow courts and litigants to immediately implement health-friendly processes and measures that deploy available technology solutions without having to change the analog nature of litigation.

1. Access to the Courts.

The Concern: Due to the need to prevent spread of the COVID-19 virus, courts remain physically closed and are accessible only by appointment. A regime of physical appearance and paper filing imposes an undue burden on litigants, lawyers, judges, and court personnel that may detract from the urgency of the reliefs sought as well as undermine the guarantee of access to the courts.

The Proposal:

IBP Support for Online Remote Hearings. IBP local chapters will provide (at no cost to the Court) the IT infrastructure that permits courts to conduct hearings remotely. This is intended to sidestep the procurement issues faced by the courts as well as the Public Attorney’s Office and the BJMP. The IT infrastructure includes the following minimum requirements:

-

- Laptop or desktop computer with a webcam, microphone and speakers;

- Internet connectivity, preferably broadband, if available; and

- Video conferencing service such as Zoom, with the IBP hosting of the session if the trial court judge is unable to do so. Alternatively, the Court can subscribe to video conferencing services through the emergency procurement provisions of the Government Procurement Reform Act (GPRA).

The IBP shall ensure that the sufficient IT infrastructure is available in the following places:

-

- Courts – for judges and other court personnel;

- Jail – for detention prisoners; and

- IBP Office – for private litigants.

To defray the costs, the IBP will charge all private practitioners a user fee. Other users, such as public attorneys, non-profit legal aid organizations, student-practice clinics under Rule 138-A, court personnel, and detention prisoners will not be charged a fee. The costs associated with their use will be defrayed from the user fees paid by the private attorneys. This is equitable because private practitioners can recover those costs from their clients.

Cloud drive is necessary to store all the virtual proceedings. This may also be procured by the Court.

Administrative Concerns

-

- Manual filings may still be accommodated. The courts can adopt a store-and-forward procedure where filings are kept in a secure area for a period of time to allow the viral threat to dissipate before the papers are physically transmitted to the court branches.

- An e-filing system or electronic docket can mirror the paper docket to avoid spreading the disease through court filings. The Court can maintain a cloud solution where documents are deemed received when uploaded by the filer. Where manual filing takes place, the document can be immediately scanned and uploaded by the receiving clerk, with the paper copy later forwarded to the branch once the viral threat dissipates.

2. Notarization.

The Concern: Many pleadings require notarization and as yet there are no rules that permit electronic notarization. On this point, as an interim measure, Rules 3, 4, 5, and 6 of the Rules on Electronic Evidence may be considered as instructive.

The Proposal: A potential solution can be composed of a process that results in a physically notarized document while avoiding physical contact between the signer and the notary public. Key elements to consider for such a process would include:

-

- The assumption that both the signer and the notary public are located in the place where the latter holds a commission.

- The signer should be able to contact the notary public, directly or with the presence of counsel, via a teleconferencing application and show the notary that he or she is signing the document, or to deliver to the notary the signed document with a photocopy of the identification used. For these purposes, email or photographic transmission of the document may be considered.

- The notary then initiates a teleconference with the signer, and possibly counsel, during which the notary confirms the authenticity of the signature by requiring the signer to sign on a blank sheet of paper and show it to the notary. The original ID can also be shown to the notary. The notary can then confirm through the teleconference the attestations contained in the verification or jurat.

- The notary may, if he or she wishes, amend the verification and jurat to reflect that he determined the identity of the signer, the authenticity of the signature, and all relevant information through a teleconference process.

- The notary can then affix his or her seal and signature on the physical document and then transmit the same to the signer. Copies of the document, identification information and the recordings of the teleconference can then be kept by the notary public to demonstrate, if necessary, the validity of the notarization process.

For simple oaths, a rule may be enacted to allow a judge to administer an oath via a teleconferencing platform. The Supreme Court may also consider enacting an interim rule that follows or is in the same spirit as the protocols above.

3. Conduct of Trial.

The Concern: Reception of evidence under current rules requiring physical appearance is no longer feasible. At the same time, the right to due process—including presentation of witnesses and confrontation—needs to be safeguarded by the judge. Finally, the judge must be in a position to appreciate the testimony of the witness and all the evidence.

The Proposal: The trial court, with the consent of the litigants, can adopt appropriate binding protocols for the reception, storage and appreciation of physical evidence, depending on the risk of viral infection they may face.

Technical concerns related to trials:

- Documentary Evidence. Comparison of copies to originals for example may be done:

- In person via representatives;

- Electronically using videoconferencing facilities; or

- On the strength of the attorney’s oath undertaking that upon pain of disbarment or suspension from use of the system, any evidence presented in electronic form is a faithful reproduction of the original.

- Presentation of Witnesses. If there is a risk of a witness being coached, opposing counsel may ask a representative to be present but if virus concerns are relevant, the parties may agree to multiple cameras trained upon the witness so that a view of his or her immediate surroundings is visible. One can, for example, require a witness to face a wall and a camera can be positioned behind him to satisfy the other litigant that no coaching is being done.

- Ethical considerations. To prevent litigants or lawyers from abusing the system for their own advantage, undertakings may be signed to enforce penalties such as disbarment or suspension from use of the system by the lawyer and his or her firm in case of suspicion of wrongdoing. This way the attorney is incentivized not only to act ethically but to avoid all appearances of impropriety.

- Criminal Cases. Special attention must be brought to the rights of the accused. Given the limitations of a short-term solution, the written waiver (perhaps supplemented by a verbal waiver secured by the judge via teleconferencing) of the accused to a physical confrontation may be obtained.

The rationale for a consent-based voluntary system is based on the inherent difficulties faced by the formulation and implementation of a uniform solution for all courts—whose circumstances are so varied. This proposal allows the IBP to move quickly and basically preserve the paper-based system but with social distancing measures built in. It requires no additional rules from the Court, although a confirmatory issuance will do well to tamp down any doubts.

_

VI. Medium-Term Considerations

While the short-term proposal is in place, the Court can then consider interim measures of rules to fine tune the system in place.

For example, the Court may enact a rule that makes the Continuous Trial Guidelines and the Judicial Affidavit Rule mandatory for this period to all cases, subject to the proposed interim rule on notarization in number 2. In the conduct of trial, the following modifications must be made to the Rules of Court:

- Rule 132, section 1 (Examination to be done in open court): Insert “remotely, as provided by these Interim Rules” into the first sentence, as follows: “The examination of witnesses presented in a trial or hearing shall be done in open court, or remotely, and under oath or affirmation, as provided in these Interim Rules.”;

- Rule 132, section 4 (Order in the examination of an individual witness): Temporarily suspend item (a) “Direct examination by the proponent” in view of the mandatory application of the Judicial Affidavit Rule; and

- Sec. 2 of the Judicial Affidavit Rule: Allow for the submission of judicial affidavits by email within a period of time provided by the judge but taking into consideration the burden of proof and the burden of evidence requirements under the 2019 Rules on Evidence (Rule 131), and the accused’s prerogative to submit a demurrer to the evidence. The prosecution can be required only to submit the judicial affidavits of its witnesses.

The judge may, after appreciation of the judicial affidavits, schedule as many trial dates as appropriate, for the defense to cross-examine the witnesses of the prosecution, who shall be presented remotely under item (a). Upon offer and objection to the prosecution’s evidence, as provided by the Continuous Trial Guidelines, the defense would then be required to provide the judicial affidavit of its witnesses unless it manifests the intention to demur to the evidence. The procedure provided in the 2019 Rules on Evidence, supplemented by the Continuous Trial Guidelines, would then apply.

The Supreme Court may also begin to develop a framework for implementing a “smart court” approach and identify which part of the court value chains can be fully transformed into e-systems using new technologies.

_

VII. Long-Term Considerations

The ECQ, the potential for recurrence of the current pandemic as well as possibility of other pandemics in the future, add impetus to the need to overhaul the judicial process, from litigation in the trial courts to disposition of appeals in the higher courts. In the medium term and long term, the court should seriously consider new technologies to improve the efficiency, accessibility and transparency of the court system. New technologies can make the court system resilient to disasters and pandemics in the long run:

- Declogging the court docket, including physically reducing the number of people who have to be present and waiting in the courtroom at any given time or day, may improve system efficiency.

- The trial process must be revised extensively to reduce unnecessary time spent in tedious court appearances. More time should be spent outside of the courtroom in pre-trial stipulation of facts, gathering and validation of object or documentary evidence, and identification and distillation of issues. Ideally, judges should be immediately focused on weighing stipulations, admissions, and object/documentary evidence without having to spend excessive amounts of time in essentially facilitating and moderating an adversarial process.

- Civil cases involving contracts, commercial transactions, and other written transactions, are often unnecessarily prolonged by tedious procedures for the introduction and admission of evidence, both written and testimonial. These procedures still reflect the older, original processes for introduction and admission of evidence which were devised at a time when courts were not as congested.

- Reforms introduced by the Court, such as the Judicial Affidavit Rule, have shortened the time it takes to present testimonial and documentary evidence by reducing the time taken up by direct testimony, but have not optimized the potential reduction in time because the process simply puts into written form pre-existing processes for presentation of evidence.

- For example, the required verbal forms for the identification and marking of documents, signatures, etc. are often still stated in the affidavit as if it were a transcription of an oral testimony in court. Written formal offers or evidence and objections thereto in separate pleadings await the prior conclusion of presentation of judicial affidavits and oral cross-examination before they can be submitted. These take up unnecessary space and time that continue to prolong the litigation process.

- Judicial affidavits are still subject to the application of rules of evidence, including objections, that were appropriate for oral testimony but are of no relevance to prepared written affidavits. An example is the objection based on leading questions, which was intended to prevent coaching on the witness stand, but has no relevance to an affidavit prepared out of court.

- Judges should be encouraged to render judgment on the pleadings where the reception of testimonial evidence through judicial affidavits will essentially work to prolong litigation. To a certain extent, they should be allowed to be actively inquisitorial rather than just passively receptive. The former will enable the judge to speed up the process of adjudication; in the latter case, which is how the court system is currently set up, it is the parties who can control the pace.

- The digitization of documents presents new challenges and opportunities in terms of ascertaining authenticity and originality. Current requirements and modes of authentication of documents are tedious and premised on manual transactions and record-keeping. Digital documentation using barcodes and QR codes will soon make these old modes and requirements superfluous. An over-reliance on testimonial evidence results in longer trials. The Rules on Evidence provide that the most reliable pieces of evidence are those that the judges can see and appreciate for themselves. Judges who are trained to analyze for themselves scientific or object evidence without the need for witnesses could help speed up the process.

- The pre-trial process for both civil and criminal cases needs to be overhauled and modified substantially, with an emphasis on discovery and disclosure as well as a strong push towards depositions which are considered admissible if presented on trial. This leads litigants to take the process seriously and, in the event of a possible plea-bargain, to consider it instead of spending an inordinate amount of time in trial. Current mandatory alternative dispute resolution (ADR) diversions do sufficiently incentivize the settlement of cases, which would be more greatly prompted by the emergence of evidence through discovery that leads parties to more realistically assess their chances at trial and the costs they would have to incur should they pursue litigation to the end.

- In other jurisdictions such as the United Kingdom and the United States, the bulk of civil litigation takes place outside of the trial process, through depositions, preparation of case folders, and pre-trial case management. The emphasis of these procedures is to facilitate the determination of facts even before trial, with the issues in dispute then already reduced to the most essential ones. Shifting the action away from trial would have short-term benefits in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, but also long-term benefit as it reduces the role of the courts and facilitates a much speedier trial with only the most essential issues remaining for litigation.

- A review of legislation and rules for possible amendment to integrate social distancing and other responses to pandemics such as but not limited to:

- Republic Act No. 7438 (Rights of Persons Arrested, Detained or Under Custodial Investigation, Republic Act No. 7438, April 27, 1992);

- Republic Act No. 8493 (Speedy Trial Act of 1998, Republic Act No. 8493, February 12, 1998);

- Batas Pambansa Bilang 129 (Judiciary Reorganization Act);

- Rules on Electronic Evidence (A.M. No. 01-7-01-SC, July 17, 2001);

- The Revised Rules on Evidence (A.M. No. 19-08-15-SC, May 1, 2020); and

- The Revised Rules of Civil Procedure (A.M. No. 19-10-20-SC, May 1, 2020).

- Work with Congress to review penal provisions for minor infractions. The continued insistence on using penal provisions to exact accountability or demonstrate an eagerness to resort to imprisonment for even minor infractions leads to overcrowding of dockets and congestion of jails. This “overload” on the administration of justice exacerbates the health risks of the COVID-19 pandemic and similar outbreaks. Congress should consider decriminalizing certain offenses and making them “civil wrongs,” with a clear system of exacting accountability through pecuniary rather than penal means.

- Reform the determination of probable cause and preliminary investigation procedures. The Court should likewise examine and recommend to the Department of Justice the review of these procedures. If the investigating prosecutor were, as a rule, the prosecutor assigned to the case for trial, the preliminary investigation would be more rigorous as there would be greater assurance that only cases supported by sufficient evidence to convict would be filed in court. The effects of the current “two prosecutor” system warrants study, as this may be an area of reform that would weed out unnecessary criminal cases before the courts.

- Adoption of new technologies including artificial intelligence (AI) tools and blockchains. In countries like China, AI tools are used to improve the efficiency and transparency of the court system.

- Mobile phone applications can be used in filing of cases, submission of evidence and communication between the parties and the judge. Pre-trial mediation, including e-signing of mediation settlement, and delivery of judgement are all done through the app.[2]

- AI tools are used to assist with non-complex court procedures like real-time recording and transcription of trial proceedings and provision of legal information.[3]

- Mobile courts utilizing new technologies should be explored further.

_

VIII. Oversight and Rule-Making

- Form a Primary Committee to Address the Issues. A primary committee should be formed in order to govern the process by which all particular issues are addressed. This will include supervision over the formation of and actions taken by the subcommittees. Preferably, this Committee should be headed by the Chief Justice with the Senior Associate Justice as the Working Chair and the Chairs of the Three Supreme Court Divisions as Members.

- Form Subcommittees to Tackle Particular Challenges.

-

- Trial Concerns. This subcommittee should examine which trial procedures can be enhanced by technology. Documentary exhibits, for example, may be uploaded into a common database and the electronic copy presented to the witness. Electronic copies of stenographic notes and key case documents such as initiatory pleadings and pre-trial orders may likewise be stored in the database. A review of all statutes and relevant rules may be appropriate in this regard.

- Evidentiary Concerns. This subcommittee should study the Rules on Evidence and the Rules on Electronic Evidence to see how the presentation of evidence by a party may be facilitated during online remote hearings.

- Criminal Cases. This subcommittee should study special concerns affecting criminal cases. These include guaranteeing the rights of the accused notwithstanding the modified procedures. This subcommittee shall likewise address the concerns of specially protected victims (e.g., victims of VAWC and child abuse) as well as those particular to drugs courts.

- Administrative Concerns. Each branch of a court performs many administrative tasks. Each strand should be studied and adapted to an electronically facilitated court process. The roles of the members of the plantilla branch staff (e.g., docket clerks, stenographers, interpreters and process servers or sheriffs), as well as that of the Office of the Clerk of Court should be re-examined or redefined in light of new changes.

- Technology Assessment. This subcommittee should assess available technologies along a slew of vectors relevant to the courts from security, ease of use, availability, reliability, and cost. Ideally, a solution that best serves the goals of electronically enabled courts should be pursued. An examination of open source software, open standards and other technologies that promote the free flow of information should be undertaken to prevent vendor lock-ins.

- Ethical Concerns. This subcommittee can examine the Code of Professional Responsibility to see their effectiveness against potential abuses from members of the bar who may want to take advantage of the gaps in processes to win their cases. Reevaluation of the Canons on Judicial Ethics may be warranted as well. Renewed enforcement of ethical rules or even amendments to the canons may be appropriate.

- Role of the IBP and Practitioners. As the national and local organization of all lawyers, the IBP has a role to play in making sure that all their members act ethically as well as to provide a sounding board for feedback on the procedures adopted by the electronically enabled courts.

- Coordination with Congress and other actors in the Justice System.

- There needs to be a realization that the justice system is not just the courts; it includes the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG) and their attached agencies. Any change to the processes must consider these agencies (e.g., Rule 112 on Preliminary Investigation and Inquest are strictly with the DOJ, yet they are in the Rules of Court; the conduct of preliminary investigation during this time is one of the processes that needs to be streamlined).

- Many reforms will require congressional action. There needs to be a coordinated effort with Congress to address these reforms.

- An economic analysis of the court system should be conducted. A serious, credible, and independent study of the economic aspects of litigation and court access must be made. This is the only way to ensure that the constitutional guarantee of free access to the courts is not diluted. The costs of bail, filing suit, and hiring lawyers are stumbling blocks towards “free” and meaningful access to the courts.

_

IX. Timelines

- Short Term (May 15, 2020 – June 15, 2020). For the short term, the Supreme Court can leave the IBP and its chapters to work out solutions that are acceptable and permissible within their own areas. The large variances between the chapters in terms of the number of lawyers, litigants, case load, quality and reliability of Internet connections, and availability of technically skilled support staff will make it extremely difficult to specify a single solution. Instead, the problem-solving can be delegated to the IBP chapters, with space and leeway to enter into arrangements with local participants to suit their needs.

- IBP. Because the short-term proposals outlined in this paper are sketches of a possible solution, it is incumbent upon the IBP to convene various committees to tackle the concerns mentioned in Part IV of this paper. Several documents need to be drafted such as binding system agreements and waivers, procedures, contracts with the Courts and other recipients of equipment and services. Ideally, the National IBP should strive to issue a starting manual that can be used as a guide by chapters to get the system running as soon as possible.

- Expected Output:

- Manual of Operations for IBP Chapters;

- Governance documents; and

- Study of all relevant Rules that pertain to trial level.

- Expected Output:

- Supreme Court.

- Support for Short-Term Solutions. The Court can aid the IBP’s efforts by providing supportive measures that permit the chapters to problem-solve and innovate. Interim rules or guidance in the form of memorandum circulars on various topics including notarization would be helpful.

- Expected Output:

- Interim Rules on Notarization; and

- An expression of support for the IBP and its efforts to transform the paper-based process into one that considers social distancing.

- Expected Output:

- Begin the work for Long-Term Solutions. The Court can convene the committees outlined above to begin the work of addressing medium term issues and the more permanent long term issues.

- Expected Output:

- Appointment of Chairmen and Members for the Primary Committee and Sub-Committees in Part VIII; and

- Formulation of a workplan with timelines for Medium-Term Solutions.

- Expected Output:

- Support for Short-Term Solutions. The Court can aid the IBP’s efforts by providing supportive measures that permit the chapters to problem-solve and innovate. Interim rules or guidance in the form of memorandum circulars on various topics including notarization would be helpful.

- IBP. Because the short-term proposals outlined in this paper are sketches of a possible solution, it is incumbent upon the IBP to convene various committees to tackle the concerns mentioned in Part IV of this paper. Several documents need to be drafted such as binding system agreements and waivers, procedures, contracts with the Courts and other recipients of equipment and services. Ideally, the National IBP should strive to issue a starting manual that can be used as a guide by chapters to get the system running as soon as possible.

- Medium Term (June 15, 2020 – September 15, 2020). In this phase, the Supreme Court can consider the issues raised in Part VI above and enact an Interim Rule to further impart validity and stability to the hybrid electronic-analog process put in place by the IBP. Meanwhile, the IBP can, with the Court’s encouragement, continue to fine-tune short-term solutions by allowing chapters to share experience and best practices. The PhilJA can also begin to provide support to judges in the form of training and other resources.

- Expected Output:

- Supreme Court. Interim Rule of procedure to support the short-term solution;

- PhilJA. Training sessions, technical support and training materials for judges; and

- IBP. Feedback loops and platform for chapters to share best practices.

- Expected Output:

- Long Term (September 15, 2020 – December, 2021). During this phase, the Supreme Court’s Primary Committee and the various Subcommittees will commence their work through consultations and research, after which they will submit their reports. From this, deliberations shall be done for the formulation of their recommendations to the Supreme Court.

- Expected Output:

- Subcommittees. Final Reports for submission to the Primary Committee; and

- Primary Committee. Approval of Final Report duly submitted to the Supreme Court en banc.

- Expected Output:

[1] Mimi Zou, Virtual Justice in the Time of COVID-19 § 2020 (2020). “Smart courts” is a policy approach first adopted by the Supreme People’s Court, China’s top court.

[2]Id.

[3]Id.

Download the PDF of “Building a Resilient Judicial System” here.

Please view the UP LAW COVID-19 RESPONSE page for all pertinent information on how we are managing our academic and administrative support during the pandemic.

on the upper right corner to select a video.

on the upper right corner to select a video.