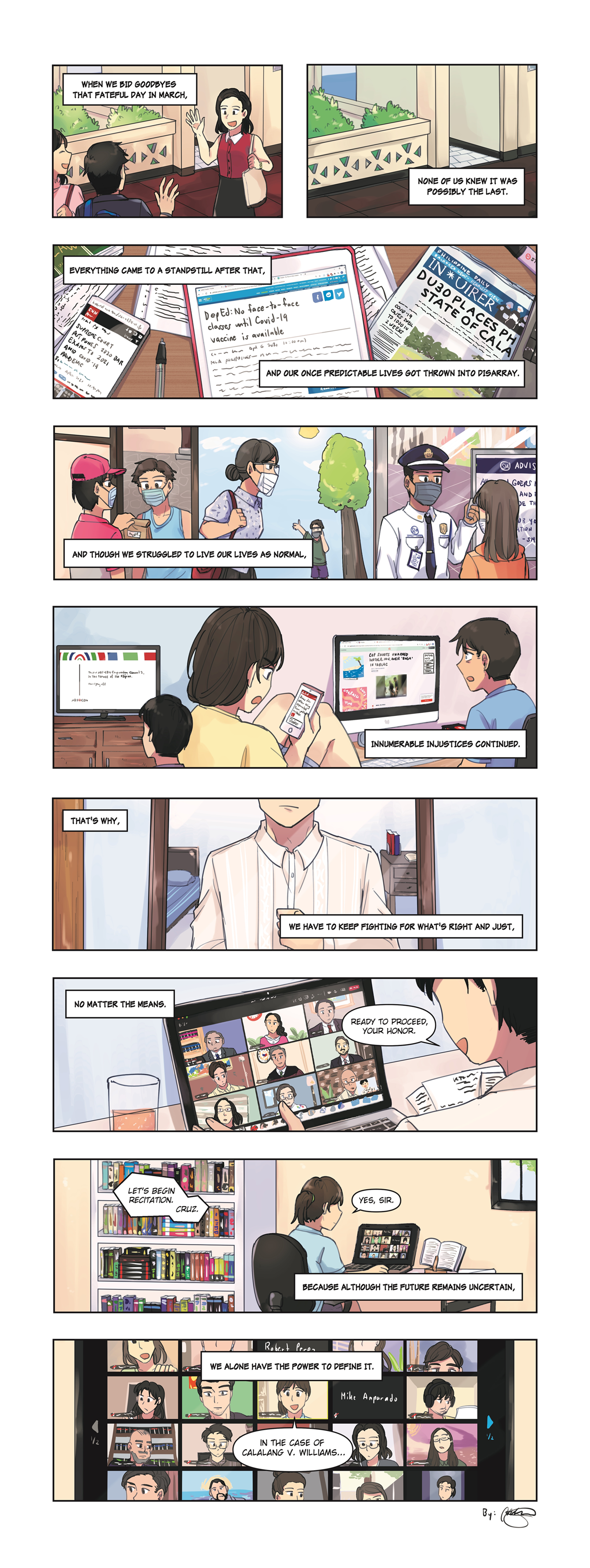

Reflections on the Bayanihan Act or Republic Act No. 11469 (“the Act”) with Matrix of Presidential Powers Under Existing Laws to Meet Emergencies, Including the Covid-19 Crisis

(5 minutes reading time, 1,249 words)

- The article summarizes the discussion among UP College of Law professors belonging to the Constitutional Law Cluster on Republic Act No. 11469 or Bayanihan Act. It also contains a comparative chart of the presidential powers in the Bayanihan Act and existing statutes.

- Emergency powers do not justify violations under the Bill of Rights, particularly freedom of expression and of the press, repression of the right against unreasonable searches and seizures, and deprivation of due process.

- The 1987 Constitution allows for a whole-of-government approach to national emergencies, with sufficient authority residing in the President who has supervision and control over the entire bureaucracy and supervision over LGUs.

- The Act delegates legislative power to the President in the context of a national emergency that prevents Congress from discharging its function. It is also a punitive measure that imposes a penalty for acts already punished under existing laws.

- The “take-over” power granted is a watered-down version of the earlier bill empowering the President to take over any business. The imposition of criminal penalty is unnecessary since the objectives of the Bayanihan Act can be achieved without criminalizing the conduct.

- Discussed within the context of Art. VI, Sec. 25 (5) of the Constitution and Sec. 4 of the Bayanihan Act, different views were given, i.e., there is no violation of the Constitution as the purpose is to give the President the power to appropriate public funds to meet the emergency, there is a violation of the Constitution since savings are only meant to augment appropriations, there are not enough statutory standards for the grant of powers in Section 4, and lastly, Sec. 23 (2) of the Constitution as an exception to Sec. 25 (5), the former triggers a “dormant” power—a constitutional dictatorship.

- The effectivity of the grant of powers, particularly Sec. 9 of the Bayanihan Act allowing the powers to be ended by Presidential Proclamation, should take note of what the Supreme Court has said in David v. Macapagal-Arroyo: “the President cannot determine when the exceptional circumstances have ceased.”

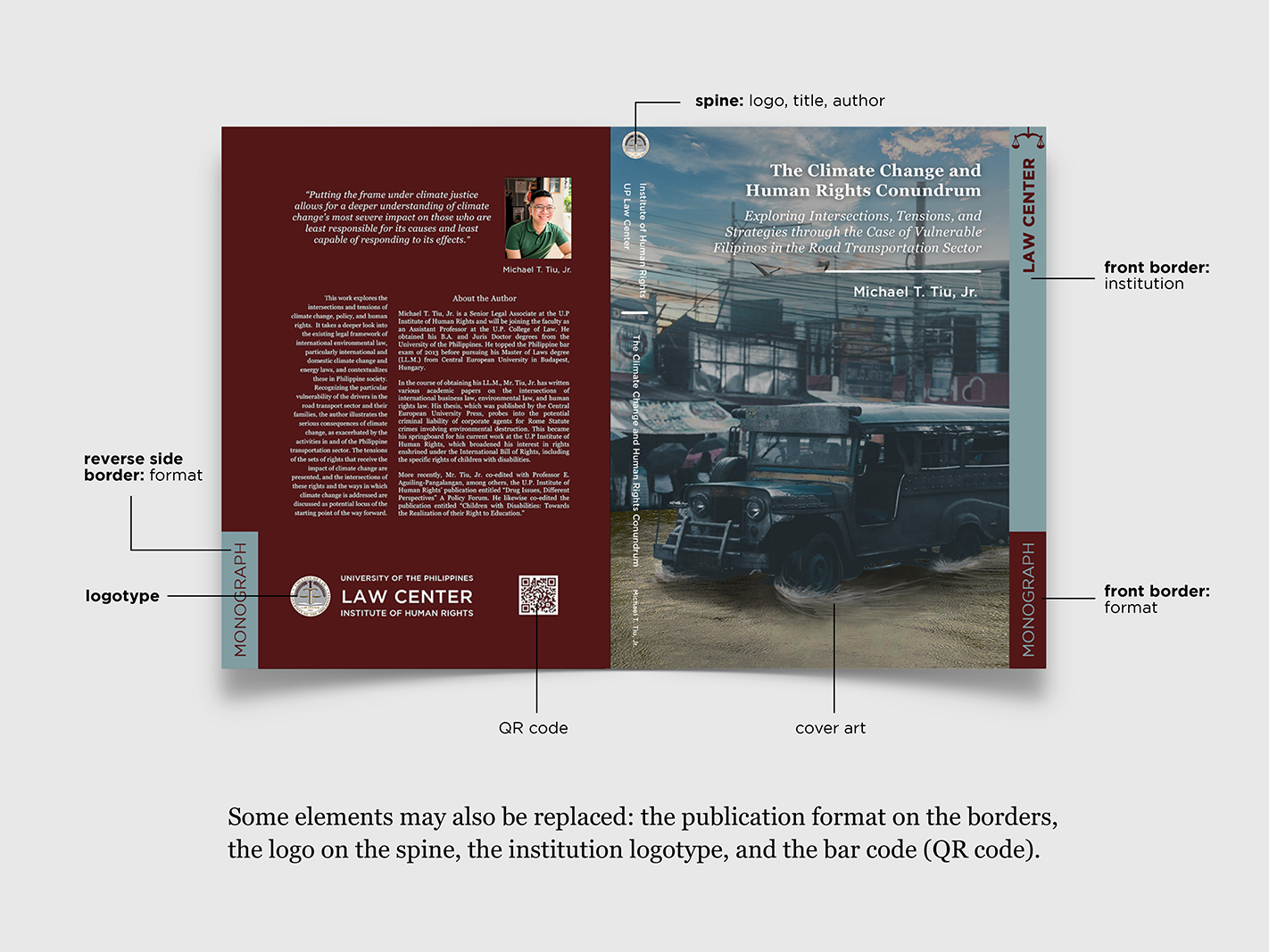

Download the PDF here (attachment includes a matrix of “Presidential Powers Under Existing Laws to Meet Emergencies, Including the Covid-19 Crisis”).

This document contains a summary of the discussion points through online engagements within the Constitutional Law Cluster [1] of the UP College of Law. It may be used to aid students, and interested parties in making their own analysis of the Act. The views contained here are not definitive and are simply meant to encourage further discussion and engagement.

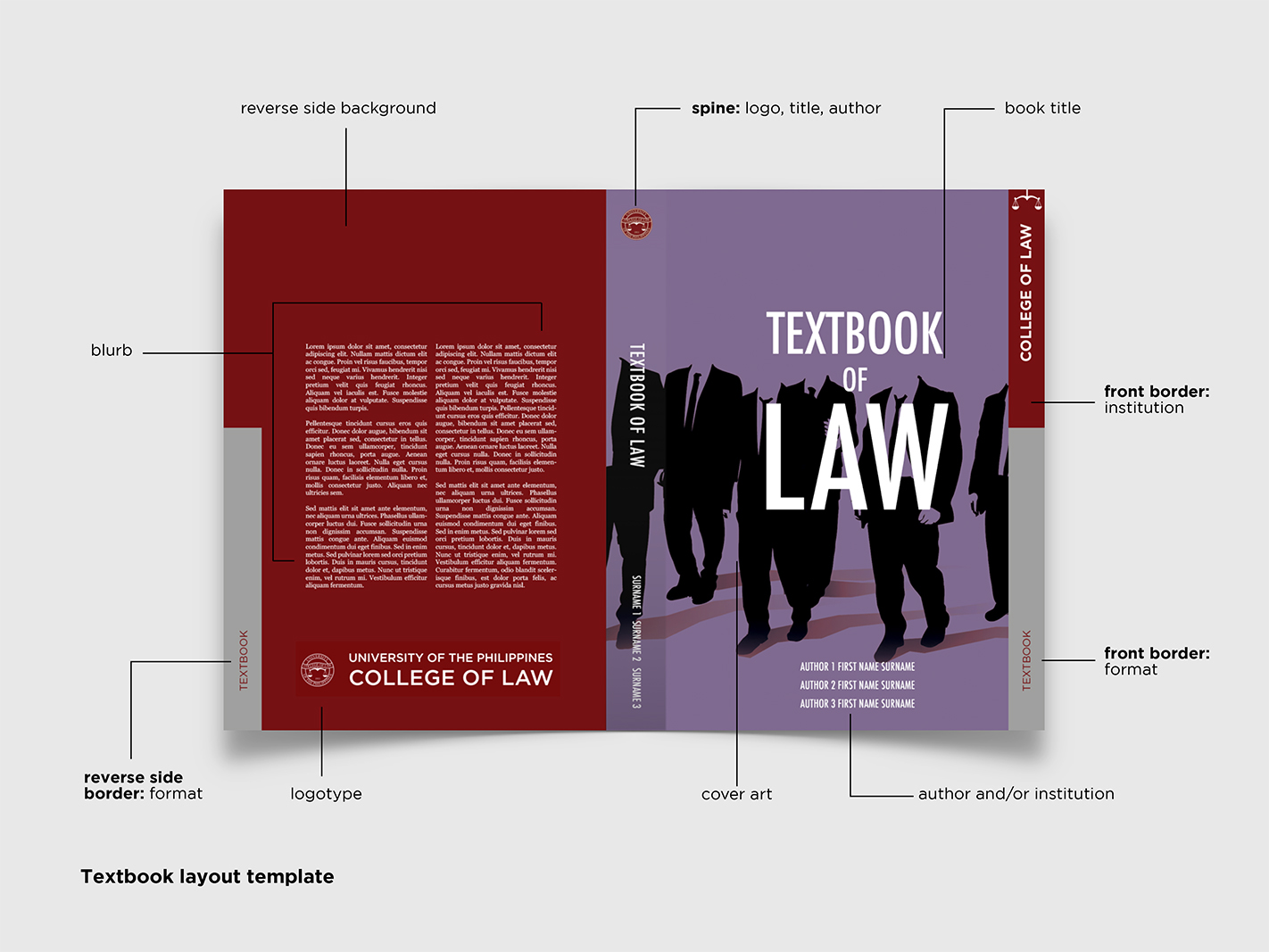

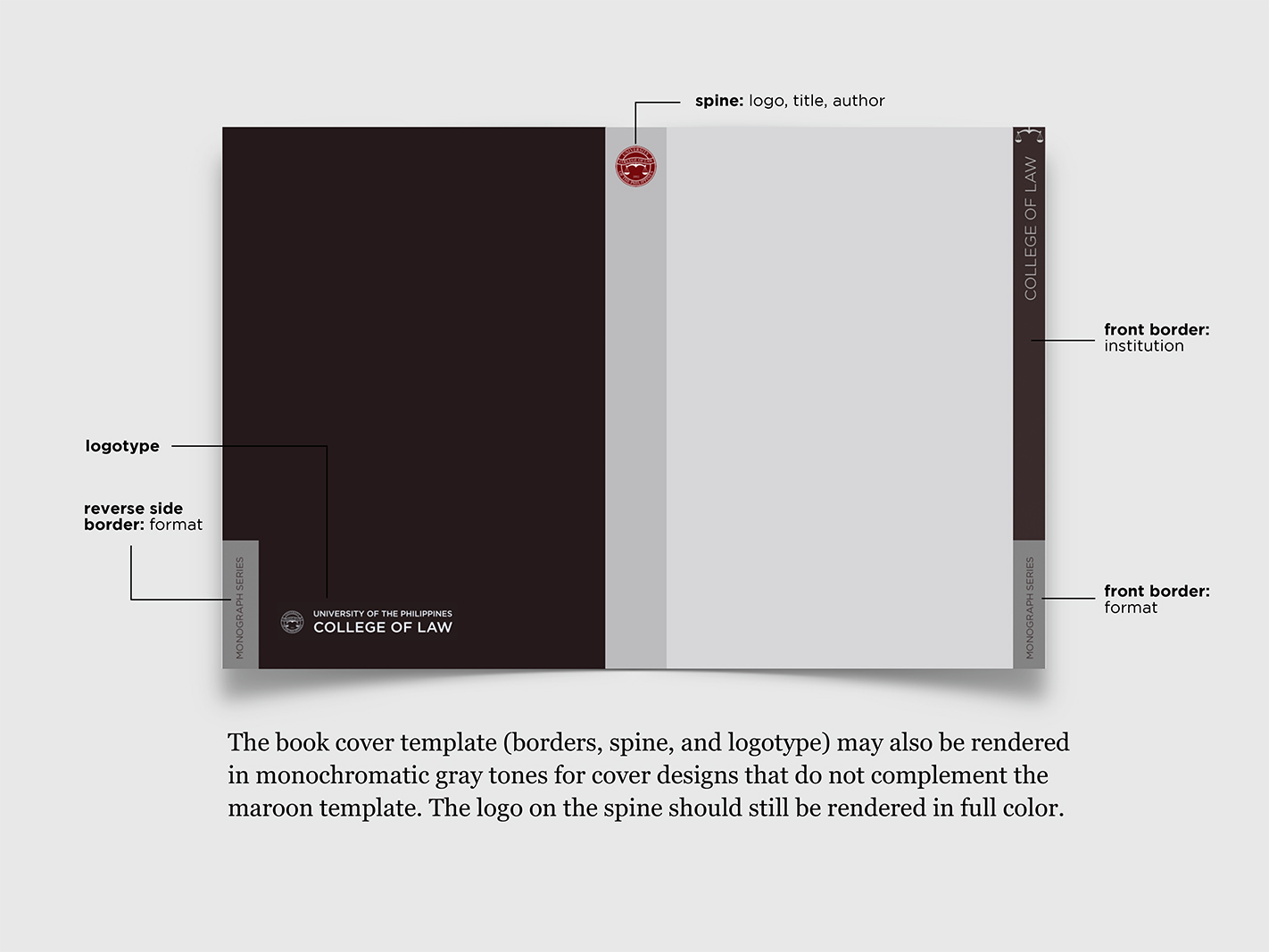

Attached to the document is a chart of Presidential Powers found in Existing Statutes that could have been used sans the Act. The chart is not exhaustive, but is meant to be a handy reference.

_

Preliminary Points on the Act

Because of previously circulating views espoused by some government officials, it is essential to begin with the reminder that the Supreme Court has ruled that emergency powers do not justify violations under the Bill of Rights, in particular abridgment of freedom of expression and of the press, repression of the right against unreasonable searches and seizures, and deprivation of due process.

Another key point raised is that the institutional structure under the 1987 Constitution allows for a whole-of-government approach to national emergencies. “Sufficient authority already resides in the President as the singular executive given supervision and control over the entire bureaucracy and supervision of local government units (“LGUs”).”

For reference, attached is a Chart of the Scope and Extent of the President’s Powers under several Existing Statutes, which allow him to perform necessary tasks to meet emergencies.

_

What the Act Does

The justification used for the Bill requires no extensive discussion. A nuanced view, however, raises that, “(t)he justification for this delegation of legislative power is the national emergency which prevents Congress from discharging its function.” This view implies that an analysis of the Bayanihan Act (and its broad delegation of powers) may proceed in the context of not just a national emergency but, one that prevents Congress from discharging its function. This dovetails with the take of another member: “Generally, Congress is the repository of emergency powers. However, knowing that during grave emergencies, it may not be possible or practicable for Congress to meet and exercise its powers, the framers of our Constitution deemed it wise to allow Congress to grant emergency powers to the President, subject to certain conditions.”

The Act is a punitive measure, which aspect may be of added interest to Criminal Law professors, practitioners and their students. Given the nature of the emergency as a public health concern, criminalizing conduct, and imposing further punitive action for acts that are already penalized under existing laws, may be viewed as oppressive and also as undue burden on government resources (law enforcement, prosecutorial service, and our courts )”.

It is also observed that the Act imposes “perpetual or temporary disqualification” from office to offenders. With elections a few years away, it was observed that this provision is prone to abuse.

_

The “take-over” power

The final version “is a watered-down version of the earlier bill that empowered the President to take over virtually any business.” As passed, it is now limited to privately- owned hospitals and medical and health facilities, including passenger and other establishments and apparently only “to house health workers, serve as quarantine areas, quarantine centers, medical relief and aid distribution locations, or other temporary medical facilities; and public transportation to ferry health, emergency, and frontline personnel and other persons.”

The imposition of a criminal penalty appears to be unnecessary considering that the President is given the authority under the law to take over the facilities. The objectives of the Act are achieved without need of criminalizing conduct.

_

Executive’s Power over Budget Items

There are different takes on the possible conflict with Art. VI, Sec. 25 (5) of the Constitution, which states in brief: “No law shall be passed authorizing any transfer of appropriations; however, the President . . . may, by law, be authorized to augment any item in the general appropriations for their respective offices from savings in other items of their respective appropriations.”

One view posits that Sec. 4 of the Act does not violate the Constitution: “In giving the President the power to ‘reprogram, reallocate, and realign’ savings from items in the Executive Department, the purpose seems to me to give to him the power to APPROPRIATE public funds to meet the emergency caused by the outbreak of coronavirus. The funds will be drawn from savings from items in the Executive Department.”

The other view proceeds thus:

“The President has been given the power to ‘reprogram, reallocate, and realign from savings on other items of appropriations in the FY 2020 GAA in the Executive Department . . .’ in clear violation of Article VI, Section 23. Savings are meant to augment appropriations, nothing more. I do not think that emergency powers can be used to circumvent provisions of the Constitution. If we sanction this provision (in the Act), then emergency powers can be used to amend any provision of the Constitution.”

Another take focuses on the statutory standards (not) given by the Act: “In general, the Bayanihan Act does not appear to have sufficient guidance for the President in the exercise of the authority granted under §§4(v-y)(dd)(ee). The creation of the oversight committee and rendition of reports are insufficient safeguards considering that the exercise by the committee of the Legislature’s oversight function of supervision is quite limited. Short of revoking the authority granted by subsequent law or withdrawing the declaration by joint resolution, Congress cannot review, modify or rescind any action taken by the President in the exercise of these powers.”

Still, another view raises the point that Art. VI, Sec. 23 (2) provides the Constitutional conditions under which Congress may authorize the President and other constitutional heads to transfer appropriations from one item to another in their respective Departments as an exception to the rule that Congress cannot authorize anyone to transfer appropriations it has made. So, while Congress cannot authorize the President to reprogram, reallocate or realign appropriations made by it, Congress itself can do that because the power to appropriate public funds belongs to it. It is this power of Congress that is expressly given to the President in case of war or other national emergency: “When a nation is at war or is a great danger, many things that can be done or said may be such a hindrance to its effort to contain the enemy or meet the danger, that the citizen must endure them so long as the need for them exists.”

This view affirms that certainly, emergencies (such as the coronavirus) do not justify violating the Constitution, but they trigger a “dormant” power — one lodged in Sec. 23 (2). “This gives rise to the occasion for the exercise of certain powers like the imposition of area restrictions, curfew hours, and the like to respond to the danger posed by the pandemic. Indeed, the Constitution provides for “periods of dictatorship” in times of great stress—constitutional dictatorship.

_

Effectivity

The largely problematic wording of the initial version has been replaced with one that gives Congress the sole power to extend the Act. Still, it was raised that a portion of Sec. 9 that allows the powers to be “ended by Presidential Proclamation,” should take note of David v. Macapagal-Arroyo, where “the Supreme Court said that the President cannot determine when the exceptional circumstances have ceased.”

See the Matrix of Presidential Powers Under Existing Laws to Meet Emergencies, Including the Covid-19 Crisis(click to download).

[1] The members of the Cluster are: Justice VV Mendoza, Tony La Vina, Alberto Muyot, Charlie Yu, Dan Gatmaytan, Gwen de Vera and John Molo.

Please view the UP LAW COVID-19 RESPONSE page for all pertinent information on how we are managing our academic and administrative support during the pandemic.

on the upper right corner to select a video.

on the upper right corner to select a video.