Understanding the President’s Treaty Powers, Senate Concurrence and Vested Rights under the recent Pangilinan v. Cayetano Ruling

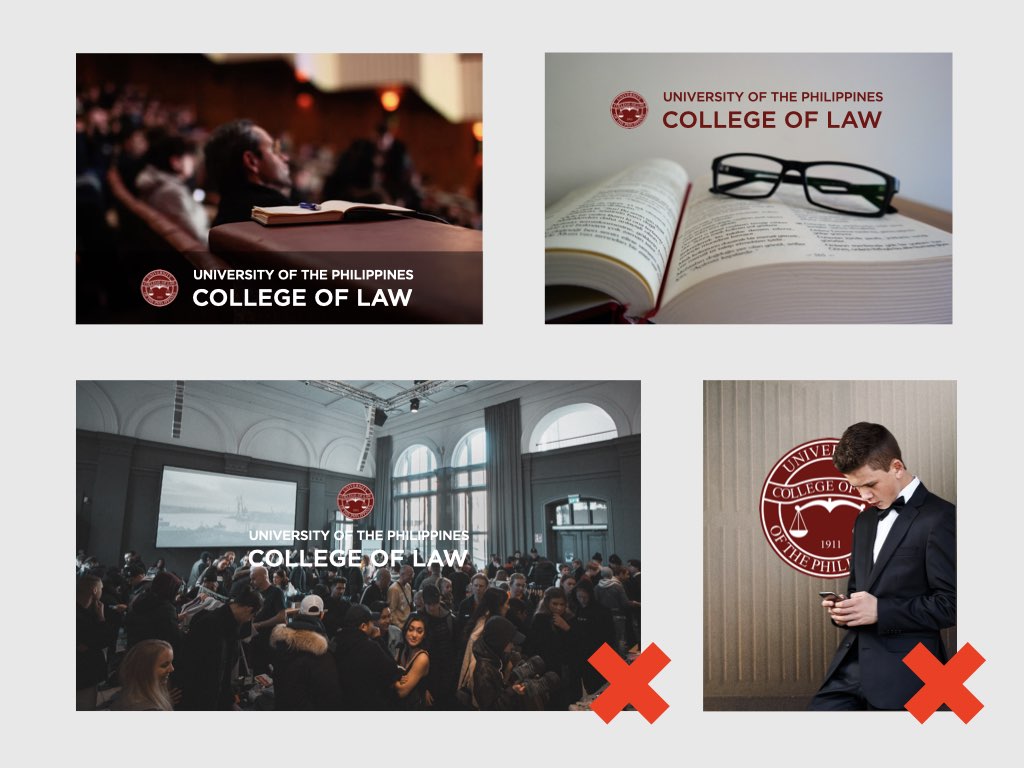

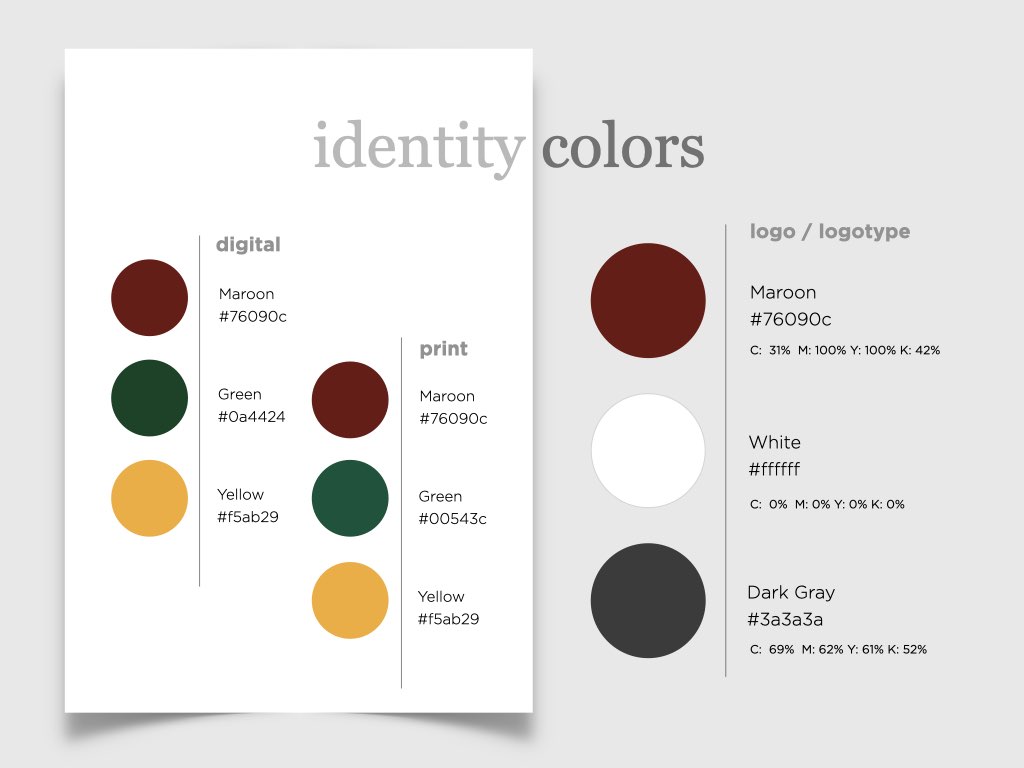

On August 11, 2021, political and international law experts assembled for an event titled “Understanding the President’s Treaty Powers, Senate Concurrence and Vested Rights under the recent Pangilinan v. Cayetano Ruling.” This was a Malcolm Lecture co-organized by the UP College of Law, UP Law Center Institute of International Legal Studies, and the Justice George Malcolm Foundation, Inc.

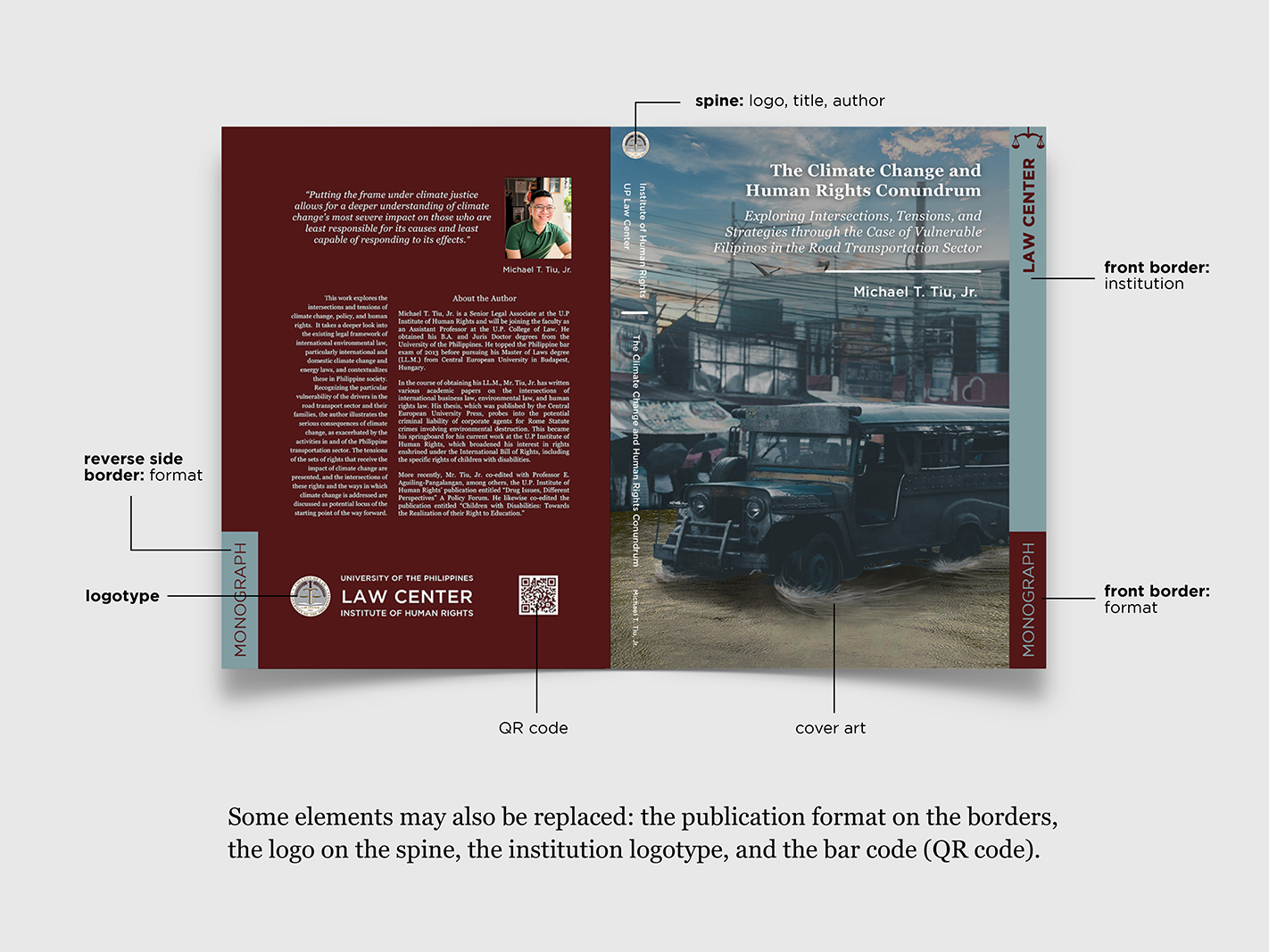

Prof. Michael Tiu, Jr. (UP IILS International Criminal Law Program Head) and Prof. Fina Tantuico (Malcolm Foundation Corporate Secretary) facilitated the Malcolm Lecture. Supreme Court Associate Justice Carpio (Ret). Justice Carpio opened the event by pointing out the inconsistency between the Pangilinan decision and settled jurisprudence. As explained by Justice Carpio, the Pangilinan Court held that the petition was moot because the withdrawal from the ICC had already been completed and had already taken effect when the petitions were filed. Justice Carpio, however, argues that this neglects the “recognized dichotomy” that domestic law applies in domestic courts and international law applies in international courts. In effect, according to the retired Supreme Court magistrate, the Pangilinan Court says that “international law prevails over the Constitution even if the withdrawal may violate the Constitution.”

The background of the Pangilinan decision was presented by IBP International Law Committee Chair and UP Law Assistant Professor Andre Palacios. He characterized the “brief event” of delivery and receipt of the notice of withdrawal by the Philippines to the United Nations as, in reality, involving a “lengthier process” that occurred in the separate regimes of international law and Philippine law. Prof. Palacios laid down significant events in a timeline that led to the Philippines’ withdrawal from the Rome Statute in 2018 to the petitions that resulted in the Pangilinan decision.

Speaking next, Constitutional Law expert and UP Law Professor Dante Gatmaytan lamented the stark incongruence of the grounds and reasoning for the dismissal of the petition with the law on standing and mootness as requirements in constitutional adjudication. He said that “the Court fashioned new technicalities so it can have a reason to dismiss the case.”

One of these novel technicalities was elucidated by Prof. Gatmaytan when he said, “Now the Supreme Court has tied standing to an institutional position to be made by Congress.” He disagrees with this because, according to him, standing attaches to an individual legislator who feels like their prerogatives are being infringed by another branch of government.

On the ground of mootness, Prof. Gatmaytan explained that “the acceptance of the ICC of the withdrawal cannot be considered a supervening event that renders a case moot. It is because there is an argument that it is unconstitutionally done. If the withdrawal is unconstitutional, nothing could have been validly transmitted to the ICC, and the ICC could not have validly accepted anything. Therefore the withdrawal was not validly done, and the case is not moot.”

Bringing international law to the fore, University of Notre Dame Professor of Law and Global Affairs, Dr. Desierto, speaking last, submitted that “Pangilinan v. Cayetano is a judicial decision of a limited effect in Philippine law, and will not affect pending ICC proceedings.” Dr. Desierto’s conclusion was grounded on the argument that much of the decision constituted obiter dicta. Only the Supreme Court’s reasoning, which led to the conclusion that the petition was moot, can be considered precedential.

Dr. Desierto explained that Pangilinan has no legal effect on the ICC Office of the Prosecutor’s (OTP) Request for authorization to investigate the conduct of President Duterte’s drug war. She said that under the Rome Statute, the Pre-Trial Chamber would determine whether there is cause to issue an authorization without prejudice to subsequent determinations on jurisdiction and admissibility. She posits that the withdrawal will not hinder the investigation of crimes against humanity committed during the time period covered by the OTP’s request.

The open forum allowed more legal luminaries to chime in what was already an interesting discussion. Justice Vicente Mendoza (Ret) said that Pangilinan v. Cayetano is “not a decision but an advisory opinion.”

“There was neither a case nor a controversy,” Justice Mendoza said.

Former ICC Judge and former UP Law Dean Judge Raul Pangalangan agreed with Justice Mendoza and further inquired on the appropriate timing of the petition filing.

“I’m struck by what the Court said, ‘the petitions were moot at the time they were filed.’ My question is, if it was too late when it was filed, what would have been on time?” Judge Pangalangan asked.

“If the President’s act of withdrawing from the statute says that at that moment there’s nothing more that the court can do, when could the petitioners have challenged anything?” Judge Pangalangan added.

The Malcolm Lecture showcased the UP College of Law’s tradition of robust intellectual inquiry and exchange. It was made possible by the University of the Philippines College of Law led by its Dean Edgardo Carlo Vistan II, the University of the Philippines Law Center Institute of International Studies, its Director Prof. Rommel Casis, and the Justice George Malcolm Foundation chaired by Justice Carpio.

View the Webinar here: https://bit.ly/UnderstandingthePresidentsTreatyPowers

on the upper right corner to select a video.

on the upper right corner to select a video.