A FORUM ON THE ICJ ADVISORY OPINION

The Obligation of States in Respect of Climate Change: A FORUM ON THE ICJ ADVISORY OPINION

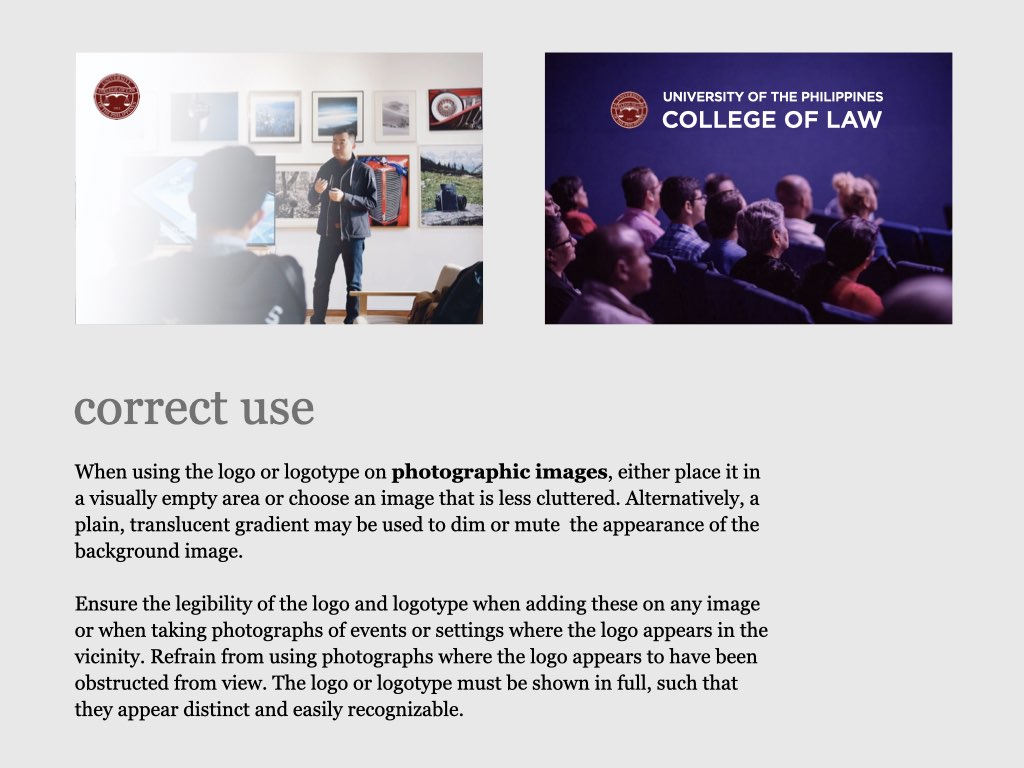

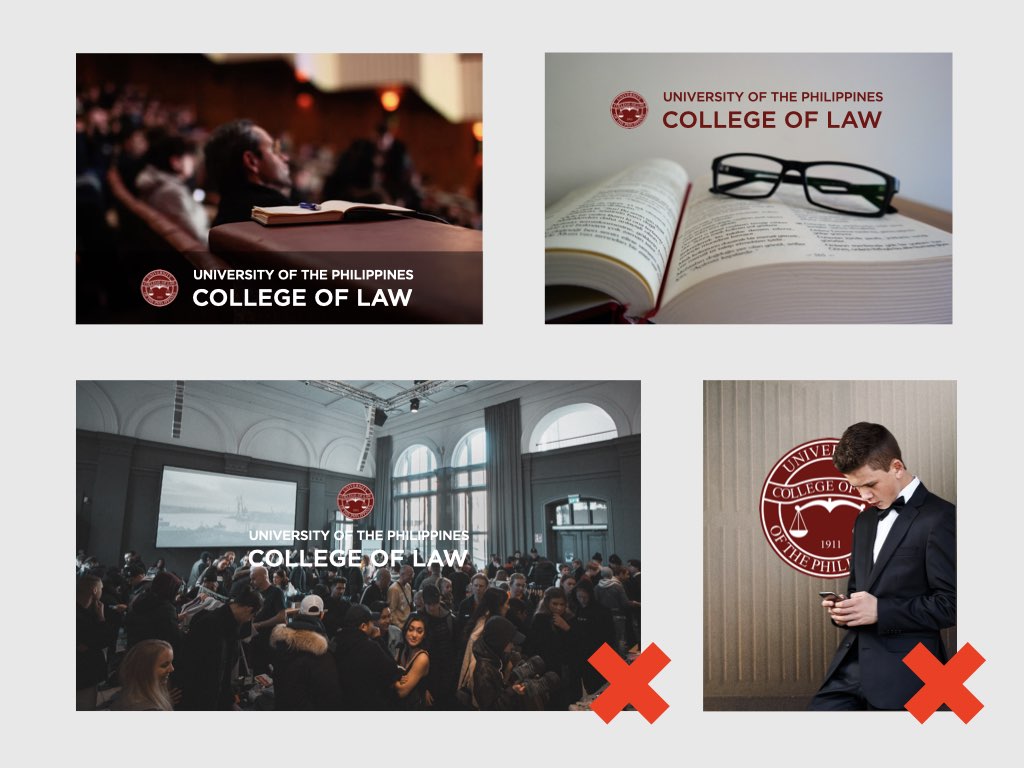

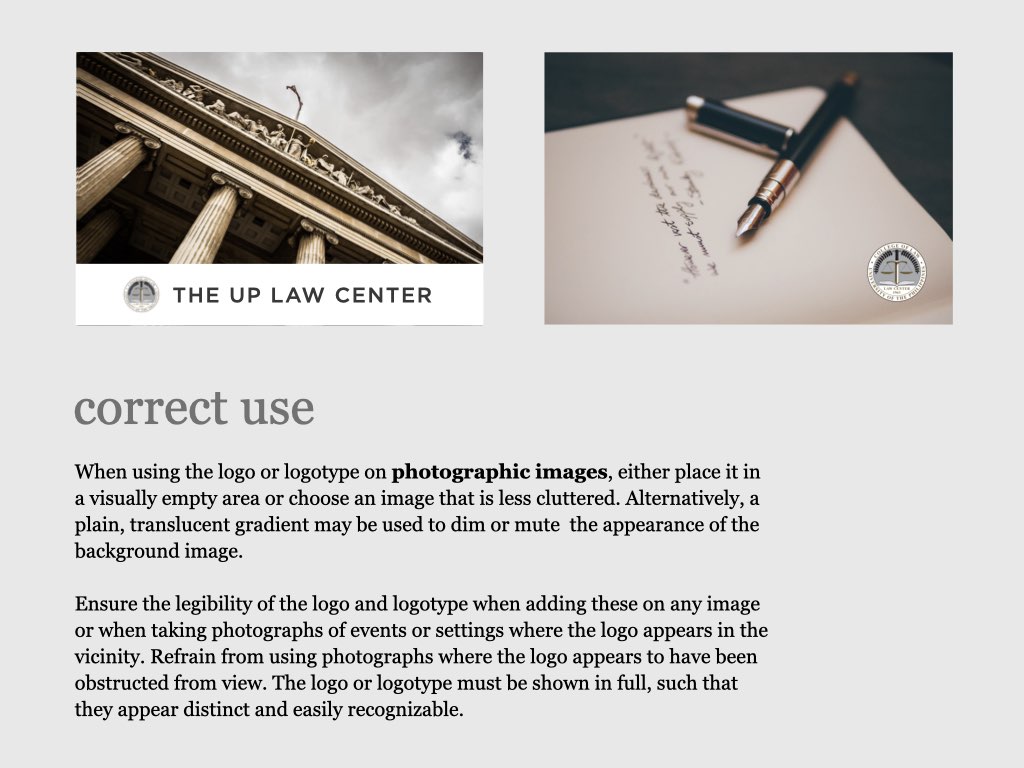

On 4 August 2025, the Institute of International Legal Studies (IILS) of the University of the Philippines (UP) Law Center hosted an online forum entitled The Obligations of States in Respect of Climate Change: A Forum on the ICJ Advisory Opinion. The Forum brought together legal academics, international law practitioners, and Philippine government representatives to reflect on the Advisory Opinion (AO) issued by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on 23 July 2025, which identified the legal obligations of States in tackling climate change. The Forum was opened by UP Diliman Chancellor Edgardo Carlo Vistan II, who explained how UP contributed to the Philippines’ involvement in the landmark advisory opinion. This was followed by insights from Assistant Professor Michael Tiu Jr, Associate Professor Rommel Casis, Senior State Solicitor Atty. Ma. Felina Constancia Buenviaje Yu-Basangan, and Director of the Environmental Security Division of the DFA’s Office of United Nations and International Organizations Atty. Johaira Wahab-Manantan. The open forum was moderated by Atty. Cecilia Therese Guiao. The discussion reflected a broad consensus that the ICJ Advisory Opinion marks a critical turning point in the legal response to the climate crisis. By reinforcing and extending the scope of State obligations, the AO provides a comprehensive normative framework that facilitates the advancement of justice and accountability across both international and domestic legal systems. The event concluded with closing remarks from OIC UP Law Dean Jay Batongbacal.

In his remarks, Chancellor Vistan emphasized a key point from the opinion: that States’ failure to take adequate climate action could constitute an internationally wrongful act. Against the backdrop of increasingly severe climate events in the Philippines, Chancellor Vistan highlighted the urgency of cohesive legal, policy, and scientific responses. He also acknowledged the important contribution of the UP Law Center in preparing the Philippine government’s submission to the ICJ, reaffirming the university’s engagement in advancing intergenerational equity and global climate justice.

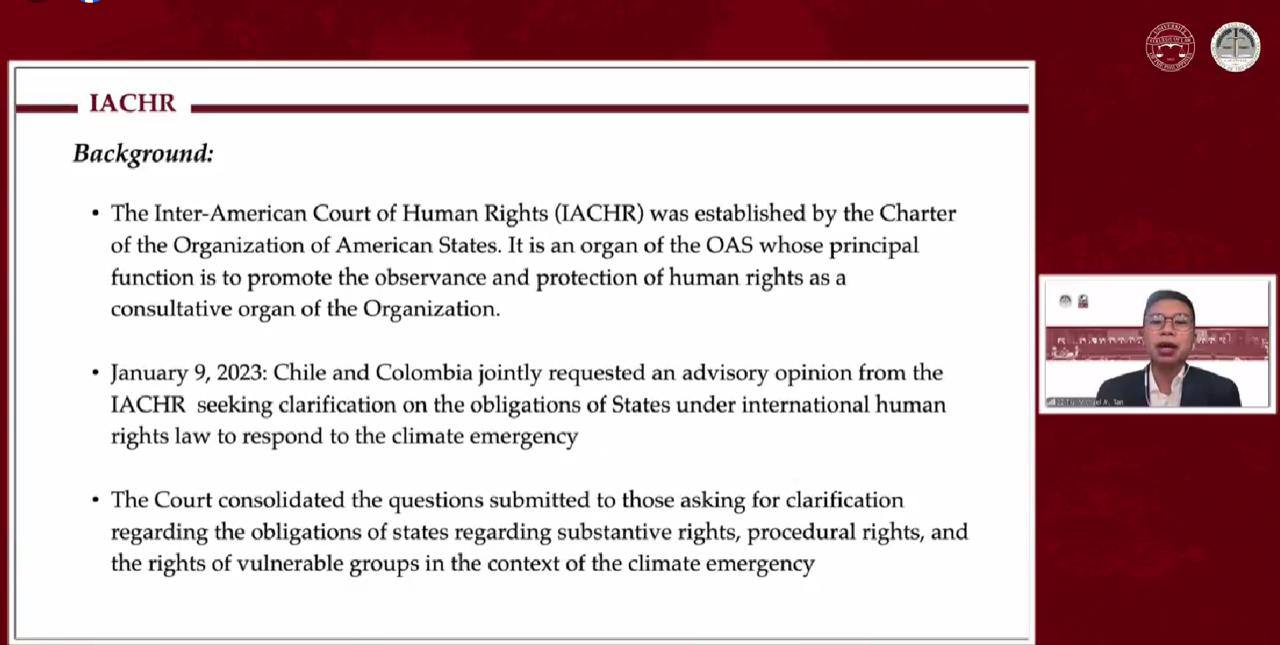

Assistant Professor Tiu contextualized the ICJ opinion within a broader set of international legal developments. He referenced opinions issued by other bodies—such as the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR)—all of which affirm that environmental degradation implicates both human rights and state responsibility. Professor Tiu underscored the ICJ’s rejection of a lex specialis interpretation— that is, the idea that environmental treaties like the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) or the Paris Agreement displace or limit the application of broader international legal norms. The Court firmly stated that these instruments should not be treated as isolated legal regimes; rather, they must be interpreted within a broader legal framework.

Associate Professor Casis described the opinion as a significant milestone in the evolution of climate law. He noted that the Court’s reasoning confirms that climate change is not solely governed by environmental treaties, but also general principles of international law—including the duty to prevent harm, the duty to cooperate, and the obligation to respect and protect human rights. He emphasized that this broader framing strengthens accountability and opens up pathways for legal redress. A key aspect of the opinion is its recognition that the Paris Agreement imposes binding obligations on States. The Court also affirmed the interconnection between climate obligations and other legal regimes, particularly the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This linkage is especially important for archipelagic states like the Philippines, whose coastlines and marine ecosystems are highly vulnerable to climate-induced harm.

Senior State Solicitor Atty. Yu-Basangan provided a detailed account of the Philippine government’s submission to the ICJ. Drawing from landmark domestic cases such as Oposa v. Factoran, she explained that the Philippines’ position was grounded not only in treaty obligations but also in constitutional protections and customary international law. The submission argued for the recognition of marine degradation under UNCLOS as a form of climate harm, and proposed that international equivalents to domestic legal tools—such as the writ of kalikasan—could enhance remedies for environmental damage. Atty. Yu-Basangan described the ICJ’s alignment with many of the Philippines’ arguments as both a legal and diplomatic success. The opinion affirmed that a State’s inaction on climate change may constitute a breach of both treaty-based and customary obligations. As with other internationally wrongful acts, such breaches carry consequences—ranging from a duty to make reparations to the requirement to cease and prevent recurrence of the wrongful conduct.

Atty. Wahab-Manantan, Director of the Environmental Security Division of the DFA’s Office of United Nations and International Organizations, reflected on the non-binding nature of the Advisory Opinion. While it does not have the force of a binding judgment, she noted it nonetheless holds considerable normative weight. ICJ advisory opinions often guide legal interpretation, influence treaty development, and bolster arguments in both domestic and international litigation. In this case, the opinion strengthens the position of vulnerable countries in pressing for climate finance, accountability, and stronger global commitments. Atty. Wahab-Manantan also underscored the opinion’s recognition that climate change is inseparable from human rights. The ICJ acknowledged that climate harms disproportionately impact marginalized communities and future generations. In this context, the Court reaffirmed principles of equity and “common but differentiated responsibilities,” which remain critical to global climate negotiations and to the legal positions of developing countries like the Philippines.

The Court’s interpretation of Article 9 of the Paris Agreement, which addresses climate finance, was particularly noteworthy. By describing it as an “obligation of result,” the ICJ signaled that developed countries must go beyond vague pledges and deliver measurable outcomes—particularly in areas such as loss and damage, where financing remains insufficient.

An open forum was moderated by Atty. Guiao, Head Legal Officer of UP-IILS. The panelists discussed the prevailing consensus that the ICJ Advisory Opinion represents a transformative juncture in the legal approach to the climate crisis. By fortifying and broadening the scope of state obligations, it establishes novel avenues for the pursuit of justice and accountability within both the international and domestic legal orders. The forum closed with a discussion on how the Advisory Opinion might influence Philippine policy and litigation. Atty. Yu-Basangan shared that the OSG had already invoked international climate obligations in defending the government’s jeepney modernization program. This suggests that global legal norms are beginning to shape not just diplomacy, but also the rationale behind domestic policymaking.

Through his closing remarks, UP Law OIC Dean Batongbacal expressed gratitude to attendees and panelists. He emphasized the advisory opinion’s significance for international environmental law and its serious implications for the Philippines, given its vulnerability to climate change. The OIC Dean highlighted the University’s pride in assisting the government in the ICJ proceedings, showcasing its commitment to international legal advocacy. He concluded by emphasizing the need for continued commitment and action to address climate change for present and future generations.

The Forum was hosted by Atty. Jurella Santos of UP IILS.

on the upper right corner to select a video.

on the upper right corner to select a video.